Introduction

The focus of this paper is the class, color, and race

components in the struggle to create a people’s music — a

music originally and essentially of the economically

disadvantaged and less formally educated citizens of

Trinidad and Tobago, primarily those of African descent. It

is based on interviews with former and present panmen and

pan women in Trinidad and Tobago and also draws on

government documents, newspapers, and personal observations

during some sixteen months of fieldwork in Trinidad between

1972 and 1985.

Music as a social phenomenon has been of interest to scholars for some time and has given rise to numerous books and scholarly articles and to several scholarly journals (for example, The Sociology of Music, Ethnomusicology and The Black Perspective in Music). Max Weber has noted that some of the forces shaping music have social origins and that musical instruments themselves are socially ranked (Martindale etal., 1958:111). Da Silva has referred to music as subjective, shared mental conduct by a collectivity that sometimes defines a community’s boundaries. He has also called attention to the conflict inherent in the social organization of music (1984:34). Shepherd has observed that an elite musical establishment of intellectuals persuades society that popular music is an inferior and less desirable art form and that music’s value is not a socially shaped reality but an ultimate one with objective criteria for judging its quality. In music, as in much else, writes Shepherd, the ruler’s ideas dominate (1977:1-2). Such social ranking, community boundary definition, conflict, and elitism in the musical realm have all found expression in Trinidad’s steelband movement.

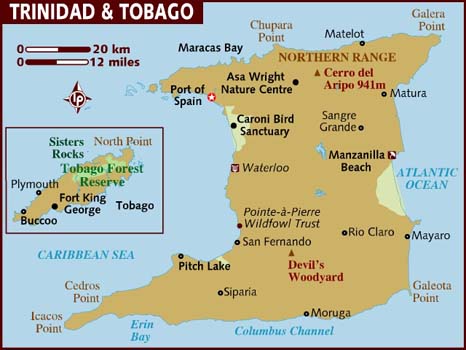

Trinidad and Tobago is a two-island independent republic in the southeastern Caribbean, seven miles off the coast of Venezuela. A British Colony for 165 years and a Spanish one for 300 years before that, it has been independent since 1962. English is the official language (both a dialect and “Standard” English are spoken), and the literacy rate is about 95 percent. Some Hindi and some French patois are spoken. Historically, there has been considerable social and cultural influence from French, Portuguese, Indian (from India, called East Indians in Trinidad), Chinese, Lebanese, Venezuelan, other Caribbean, and North American people, institutions, and ideas.

Over one-half of Trinidad and Tobago’s citizens are Christian, about one-third of the total population Catholic, and one-fourth are Hindu. About the same percentages of Trinidadians (41) are East Indian and Negro (the official term used there), about sixteen percent are of mixed ethnic/racial heritage, and about one percent is white. Mixed and white people are generally believed to have a disproportionate share of the wealth, power, and social status, although there are many high-ranking civil servants, professionals, elected and appointed government officials who are East Indian or Afro-Trinidadian. The late Dr. Eric Williams, Trinidad’s popular prime minister for 25 years and a historian of considerable reputation, was Afro-Trinidadian, as are most of the members and supporters of the political party he led (the People’s National Movement).

Steeldrums are called steel pans or just “pans” in Trinidad and Tobago. Beginning in the 1930s, they were created and refined in the poorer sections of Trinidad’s capital, Port of Spain, by young men of African heritage with little formal education or musical training. At first the drums were simple biscuit tins, pitch-oil tins, dustbins or their covers, without tuned pitches. Gradually, through experimentation and refinement, pitches were added by pounding in and out on the top surface of the drums, and drums of varying depths were created to produce different ranges.

Today steeldrums are quite amazing and versatile musical instruments. The small tenor pans may have up to 32 different pitches. Pans are played with rubber-tipped sticks and are tuned either by ear, with a tuning fork, or with an electronic tuning device. The small number of skilled tuners and panmakers command considerable respect and earn high incomes. Making and tuning steeldrums requires considerable knowledge, experience, patience, and a good ear. The proper raw material must be carefully chosen, the top hammered down to a precise depth, notes carefully marked in, sometimes with calipers, the drum cut down to the correct size and tuned, and the metal tempered by throwing water or oil over the drum while it is in a fire. According to a 1952 government report on the steelband movement, “The magician behind this wizardry of sound is the ‘tuner’ who, with his uncanny sense of ear, tempers and pounds the metal until its notes respond to the tonal pattern deep in the recesses of his soul.” (Farquhar, 1952:1)

The tuning of steeldrums is not standardized, so it is usually not possible for two or more steelbands to play well together unless their drums have been tuned by the same person. The number and position of the notes on the drums vary from tuner to tuner, and the pitches on some of the drums are not arranged in chromatic order, which facilitates striking the notes with the rubber-tipped sticks. Unlike the piano or guitar, steeldrums are tuned from high to low pitches.

There is wide variation in the types and combinations of steeldrums used in a given ensemble, depending on the occasion and the personal preferences of the band leaders and arrangers. Following are the basic types of drums and their voice parts:

-

The tenor pan, also known as the melody pan or the ping-pong, approximates the soprano voice and plays the melody. It has from 28 to 32 pitches and is about six inches in depth.

-

The double tenor is a set of two tenor drums, which play harmony and counterpoint and are about one-half inch longer than the single tenor.

-

The second pan is in the alto voice range and about eight inches in depth.

-

Double seconds play harmony, in a set of two drums, providing the upper register of chords.

-

The guitar pan plays rhythm and has about sixteen pitches. It is about fourteen to sixteen inches in depth and is played in pairs.

-

The cello pan is in the tenor voice range, about twenty-one inches in depth, and played in sets of three, with eight, eight, and five pitches, respectively.

-

The tenor bass plays rhythm, in sets of four, with two or three pitches on each drum. It is about five inches shorter than the full bass pan.

-

The bass pan is the full size of the oil drum and plays rhythm in sets of six or nine. Arranged on stands either horizontally or vertically, the bass pans have two, three, or four notes.

A steelband might also include a set of trap drums, some congas, bongos, maracas, and a piece of steel or heavy iron (sometimes an automobile brake drum), played as a percussion instrument with a piece of steel or an iron bar. (Keer, 1981:1-2; Mahabir, 1986:33; Seeger, 1961:22)

Because pan music is almost always played by ear, band members, who today include more women, East Indians, mixed and white people than at the start of the movement, must attend long and frequent rehearsals to memorize their parts for the repertoire. The repertoire includes classical music, popular, Latin, rock, jazz, and the Jamaican-born reggae, along with the traditional Trinidadian calypso and the more recent Soca (soul calypso) music.

Color,

Race, and Class in Colonial Trinidad

Class, color, and race

conflict over musical styles, preferences, instruments, and life-styles

emerged as early as the 1800s in colonial Trinidad and continues in a

milder form today. Although some see the conflict as a socioeconomic

rather than a color or race issue, color and race have also played an

important role. In British colonial Trinidad in the 1800s there was

considerable prejudice and discrimination against people of African

heritage, whether slave or free, colored or black. Brereton observed

that under Governor Picton in 1802:

“The coloured militia officers…were stripped of their rank, the troops were racially segregated with…exofficers put under a white sergeant. They had to get police permission to hold a ball and (had to) pay a discriminatory tax… A curfew at 9:30 P.M. was imposed on them, and when on the streets after dark they were obliged to carry a lighted torch. They could be arrested if found carrying a stick on the streets. Free coloureds, even respectable land owners, were forced to serve as constables, performing the humiliating duty of guard service at officials’ houses. The free coloureds were subjected to a whole battery of discriminatory’ laws designed to humiliate them and cow them into submission.” (1981:49)

Errol Hill has observed that for centuries in Trinidad, Europeans have been afraid of any sort of diversions that might “incite the passions” of black people. Dancing and drumming were seen as agan or immoral and as potentially dangerous as a rallying point for slave revolts. Drumming was outlawed in Jamaica in 1792 and in Tobago in 1798. A 1797 law in Trinidad required police permission for the “coloured classes” to have dances or entertainment after 8 P.M., and slaves could not even apply for such permission (1972:33). Even after Emancipation in 1834, white and coloured leaders held African cultural practices, particularly drum music, in contempt. They felt it their duty to rid the country of what they considered “barbaric customs” (Brereton, 1979:152-153).

Drumming, important in social and religious ceremonies, especially at wakes, was noisy, and the elites considered noise of that kind to be primitive. Drumming was important also to Trinidad’s East Indians, so this was an instance of cultural as well as class and racial repression. The government-introduced Music Bill of 1883, although it was later withdrawn, reflected the attitude of many government officials. It would have banned drumming after 10 P.M., but allowed the playing of European instruments by license. Between 6 and 10 P.M. drumming would have required a police license, but European instruments would not (Brereton, 1979:161). An 1883 ordinance outlawed “singing, dancing, drumming and other music-making by …rogues and vagabonds or incorrigible rogues” and called for the punishment of the owners of dwellings or yards that allowed it (10 July 1883 Amendment to Ordinance No. 6 of 1868). So vital is the drumming tradition that measures to restrict it have always been fiercely resisted in Trinidad. Between 1881 and 1891, there were several violent clashes between the police and the people, both East Indians and those of African heritage, over the use of drums in religious and social observances. In one of these, twelve persons were killed and over 100 injured (ibid., l84). Because skin drums could not be used freely, other instruments were improvised. In the early 1900s, the “tamboo bamboo" (bamboo drum) band was developed. Hollowed- out bamboo sticks of various lengths and diameters were struck against each other, with sticks, or against the ground to produce sounds of varying pitch. Bottles and spoons were used for higher-pitched sounds. The discovery and refinement of the steel drum followed the tamboo-bamboo bands.

The Development of the Steeldrum

Trinidadian artist Patrick Chu-Foon recalls the early tamboo-bamboo sounds and the beginnings of the

steeldrums:

“Long before even steelband came out, I remember seeing the bandsmen thumping bamboos on the raw

pitch, the asphalt on the street. I used to stand at the top of my father’s shopfront and look down into the

street and see all the goings on of early carnival… I remember the sounds. Maybe this is where the African

influence comes in, because it was a thumping, a thumping of the drums… They also had some skin drums.

This was also the early beginnings of steelbands.” (1983:1)

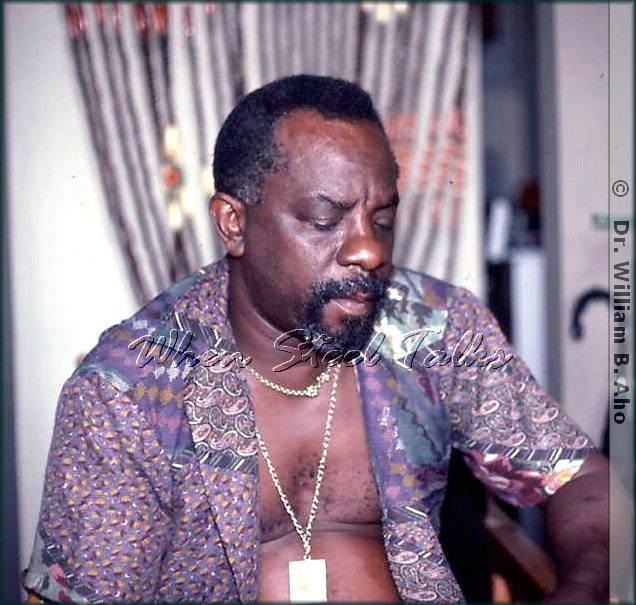

The Roaring Lion

Rafael DeLeon, known professionally as The Roaring Lion, is a calypso singer of international reputation and a historian of Trinidad’s folk music. When I interviewed him in 1983 when he was age 76, he recalled that people in Trinidad had been beating on metal and tin for some years before the steel drum itself was created:

“Long ago and to some extent up to now, children used to get together on Good Friday and make an effigy of Judas. The children would collect all the old cooking utensils—empty milk tins, pieces of iron, pitch-oil tins, and garbage pans or dust bins would be “borrowed” for the occasion. They would march back and forth through the district beating their pans while they sang …and the rhythm of that pan was identical with what is now known as the steelband, even up to the middle 1940s, before they started to discover notes and produce bits and pieces of melody.” (1983:1-2)

He further reports that around 1930 the members of a tamboo bamboo band led by David Leach, from George Street in Port of Spain, “would pick up garbage pan covers, pieces of steel from the ‘smith shop in George Street, and any cooking utensil they could find and proceed to beat it in time with the rhythm of the tamboo-bamboo” (ibid. :3).

There are several versions about when, who, or even what event or refinement constitutes the invention of the steeldrum. Oscar Pile (aka Oscar Pyle), pioneer steelbandsman and the organizer and leader for many years of the Casablanca steelband, claims that:

“…way back in 1935 they had the tamboo-bamboo and playing on the road, by an accident, one of the leading men, which was Forde, was playing one of the bamboos. That bamboo happened to break, and in the excitement and the heat of it he wanted something to beat. He then run across the road and take up a dustbin cover, and by beating the dustbin cover they found out really the dustbin cover had a more stinging and more rhythm sound than the bamboo just knocking on the ground and from then on that particular band from Newtown, Alexander’s Ragtime Band, they then went back and they start looking for pans …old paint pans and so on and getting a more genuine sound than the bamboo. Whilst they was at that, Gonzalez (a district in Port of Spain) went and start making pans and getting pans, old disregarded bins, biscuit drums, gasoline tanks, and so on, and this was the birth of the steelbands.” (1983:6)

The crucial point in the

transition from bamboo to steel is probably when different pitches were

added to the metal drums and melodies could be played on them. There is

a consensus that the first pan with notes was created in the mid-1930s,

evidently by accident, and that one of the first, if not the first, to

add notes and play recognizable songs was the late

Winston “Spree”

Simon, who is accepted by many Trinidadians as the “father” of steelband

music. Here is his version of how notes were added to the crude pans:

“I had lent this drum and on coming back to retrieve my drum, the face

of the drum was beaten in so badly that it had taken on a concave

appearance. Now I just took the drum and went on the side of the road

and tried to get back the face of the drum to its normal surface. By

pounding on the inside with a stone and a stick, in and out, I

discovered that I was able to get four distinct notes, which enabled me

to play something of a bugle call—and therefore I played at that moment

(a short bugle call).” (Martin, 1981)

Steelband music—the discovery and evolution of the instrument itself, the bands that played it, and the entire social organization of the band, its followers and supporters, and, in many cases, virtually the entire community where the band was based—was a product of the underprivileged areas, primarily in Port of Spain, inhabited almost entirely by people of African heritage. Young people in these areas did not have much opportunity for recognition, success, or self-fulfillment in the customary areas of achievement—education, job, or career—so they channeled their energies and talents into whatever areas were available to them, in spite of, in some cases, precisely because of, resistance by the ruling colonial government and elites. In the case of steelband music, they were using their own distinctive culture, instruments and music of their own creation, to express themselves and to define an acceptable and comfortable social location for themselves in their own eyes, in the eyes of their peers, and in the eyes of the communities in which their bands were based.

George Yeates, leader of the

Desperadoes steelband during the 1940s and 1950s, elaborated in an interview on the economic and social conditions of the early band members:

“Those were the colonial days and …the boys didn’t have much education …they just reached of age for primary school and they left and were all unemployed, without a skill… The steelband was the only pursuit at the time a young man could have involved himself in and sort of gave a status to a village youth so that when you come from Desperadoes or the Laventille Hill and you go to another district if your band is a powerful band, you will be respected.” (1983:3)

At the time that the steel drum was being refined, in the mid-1930s, there was considerable political and labor unrest in Trinidad. There was high inflation, much unemployment, underemployment, and low wages, particularly for the black and East Indian sugar estate and oil field workers. There were strikes, hunger marches, and, in 1937, a labor riot. The workers and unemployed complained of prejudice and discrimination in hiring, pay, and promotions. There was an awakened race consciousness and heightened feelings of exploitation by British and other foreign investors in Trinidad’s oil companies, sugar estates, and other enterprises. The Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935, unopposed by the Western nations, served as a stimulus throughout the West Indies to black nationalism and support for Ethiopia (Brereton, 1981:174). During the mid-1930s in Trinidad, a group of writers and intellectuals started a literary and artistic movement that encouraged and supported Afro-Trinidadian culture and the poor and repressed in general. This entire political, social, artistic, and intellectual milieu very likely stimulated or, at the least, was very consistent with the development of the newly-emerging steel drum as an innovative musical creation of poor Afro-Trinidadians.

The Social Importance of

the Steelband

The importance pan players attached to their

activity, and the role it played in their self-image, is reflected in an

anecdote told by Trinidadian writer, patron of the arts, and politician,

the late Albert Gomes. As a high-ranking government official in the

early 1950s, he was asked by the girl friend of a young pan player

condemned to hang for murder to intervene on his behalf. Gomes saw the

youth and learned that he had killed another young man in a rage because

the man had told him that he didn’t know anything about steelband or how

to beat pan (among other insults). The prisoner was hanged (1974:96).

Trinidadian novelist Earl Lovelace, in The Dragon Can’t Dance, poetically describes the preparations being made by young men for the important annual carnival celebrations:

“Now the steelband tent will become a cathedral, and these young men priests. They will draw from back pockets those rubber-tipped sticks which they had carried around all year, as the one link to the music that is their life, their soul, and touch them to the cracked faces of the drums.” (1979:12).

Panmen have been celebrated in poetry as well as prose in

Trinidad, as these excerpts from Sugar George,

by Paul Keens-Douglas, show:

Ah was dey when dey bury Sugar George

When he get de fus’ piece ah property he ever own,

Six foot of hard, dry Trinidad soil . . .

De pans was playin’

When George dead dat nite,

Beatin’ de dark wit’ notes so sweet

Ah fittin’ death for Sugar George,

For he was ah man, ah real man,

An’ more dan dat ah steelban’ man.

An’ now Sugar dead an’ gone

An’ ah see him lyin’ dey on de bed,

De greatest Tenorman in Trinidad,

As poor as de day he born,

Yet richer than any millionaire in de land,

More respected than any politician,

For Sugar was ah something, ah somebody,

He was part of ah plan

Dat we eh even begin to understand …

Before he dead he say ‘beat pan.’

So dey beat when he sick,

An’ dey beat when he dyin’

An’ dey beat when he dead,

And when dey finally put Sugar away,

Every band in Trinidad play.

An’ ah swear to Jesus ah could hear Sugar tenor playin’

softly, softly,

An’ Sugar laughin’ …’’

(Keens-Douglas, 1979:34-35, 37)

Celebration of the lives of steelbandsmen at their deaths is not confined to poetic representations but is a fact of real life in Trinidad. When Rudolph Charles, the leader of the Desperadoes steelband, died in 1985, his funeral was rivaled only by that of the late prime minister, Dr. Eric Williams. The media mourned him as a national hero, and his body was drawn through the streets of Port of Spain in a casket fashioned from two large steeldrums. Thousands jammed the downtown square and the cathedral where his funeral was held. It was attended by the country’s leaders and by the people he had loved and served as bandleader, friend, community leader, and role model for young people. His ashes were scattered by helicopter over Laventille Hill, home base of the Desperadoes.

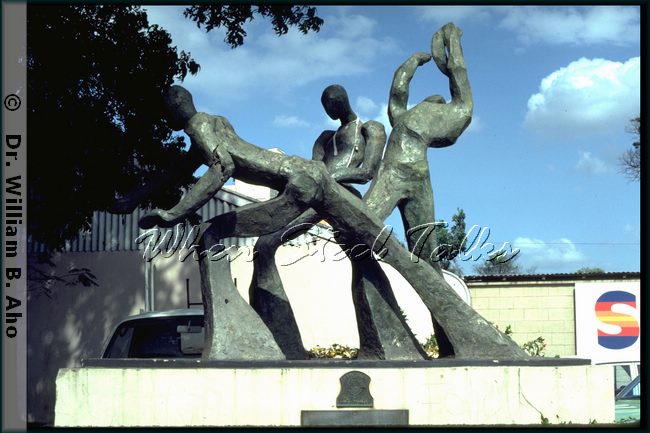

Chu-Foon Pan Sculpture

Steelband has also been honored in the other arts. Patrick Chu-Foon’s sculpture Tribute to the Steelband in Port of Spain, Errol Hill’s drama The Ping-Pong, and the well-known oil painting Steelband Boys in White by Boscoe Holder are just three of the better-known examples.

An example of the enduring pride former steelbandsmen often have in their bands was revealed to me at a professional meeting by a Trinidadian university professor employed in Canada. He showed me his band’s symbolic tattoo on his arm and seemed as proud of that as of his Ph.D. degree.

The Interim Report of the Committee to Consider the Role of the Steelband in the National Life reported that the steelband movement brought not only a knowledge of music to its adherents:

“It contributed the discipline of band organization and of steady practice to persons who might never have had such opportunities to acquire skills and disciplines fundamental to proper adjustment to a progressive role in society. Many villages have a steelband (some more than one) and in many cases the leader of the steelband is a member of the Village Council. There appears also to be great willingness on the part of the Village Council to cooperate in such things as the putting on of concerts involving the steelband and the loan of the Community Centre for practice sessions by the steelbands… Most rural bands also make it quite clear that they were established for musical enjoyment. The urban bands have become quite commercialized and specialized and as a result do not form as integral a part of community life as do the Village bands (with the exception of Desperadoes and Casablanca).” (1965:9,11)

These findings point out an important factor—that at least some of the urban bands, and many, perhaps most, of the rural ones, play an important role in the community. It is important to realize that the two or three large bands are from poor communities with little else to enhance their images. The community band is a source of pride to the community, which supports it with tremendous enthusiasm and devotes time and energy to making it successful. Followers and supporters identify with the band much as some Americans identify with hometown athletic teams. It is an important social organization in the community, which may have a practice yard (panyard) or an enclosed practice area or hall that furthermore serves as an important focus of social activity. Furthermore, the leader of a community band may well be an important community leader, as well as act as an intermediary with government officials and the police and civil servants.

Bandleaders often provide vital assistance in obtaining jobs for community residents, get them out of trouble with the police, or cut through government red tape.

Rudolph Charles

Rudolph CharlesOne such leader was the late Rudolph Charles of Desperadoes. Journalist Peter Blood has observed that: “The panyard of Desperadoes stands precariously nestled atop the lofty heights of Laventille Hill, overlooking the city of Port of Spain. Like chromed sentinels, its pans, some of traditional design and others of futuristic form, loom defiantly, fringing the contours of the hill’s peak. Pan is a way of life on the Laventille Hill and Desperadoes provide the lifeblood for this vibrant and creative community… Beside being the band’s captain, [Rudolph] Charles also tunes the band’s low pans, and is regarded, amongst other things, the godfather and the sole lawmaker of the hill.” (Blood, 1983:62)

Schoolteacher Rudy Piggott, at Rudolph Charles’s funeral, claimed that, “Rudy was the Moses of the people of Laventille. We do not even need the police there. Rudolph was a leader and he controlled us all.” (Piggott, 1985:3). Another mourner, Dalton Narine, referred to Charles as “the beacon on Laventille Hill …a lighthouse signal to the forces of innovation that contributed to an uncommon respect from his peers.” (Narine, 1985:3) Journalist Meryl James Bryan referred to Charles as “a fallen leader—appointed African style by a council of elders” and as “the General of one of urban Trinidad’s most African populations. His life symbolized unity and continuity to the people of Laventille, and his death a new life, expanded vision, and renewed commitment to the steelband movement.” (Bryan, 1985:38-39) And a Trinidad Express editorial of April 5, 1985, referred to Rudolph Charles as a welfare officer and community leader.

In a 1985 interview with a prominent business executive very closely connected to Rudolph Charles’ Desperadoes band, it was observed that:

“Charles was an exceptional leader. Dynamic, with personal magnetism and good managerial talents. It was hard to refuse him what he asked for his band. He was a genius in steelband, an innovator. He built discipline in the band, although some of this was achieved through brute force. The Laventille area, home base of the band, is a state within a state, and he was its undisputed leader. He dispensed money and aid on the Hill like a politician.” (Anonymous 1, 1985:1)

Another very close Rudolph Charles confidant, who also asked

to remain anonymous, said that he was a

very determined person, had an inventive brain, and that

though he used physical strength at times to

enforce discipline, he was accepted and respected.

“He would intervene in court and at police stations to help

his followers. The doors of government ministries

were open to him. He was a skillful manager and a born

leader. He even ruled Laventille while he was

away, living for most of the last several years in Los

Angeles. He worked with the village elders, outside

the legitimate county council.” (Anonymous 2, 1985:1).

Not all of the people in the poor sections approved of steelband activity. Some had adopted the attitudes and values of the ruling elite toward noise, drumming, and the entertainments of the poor African masses. Others, often parents of young people, didn’t want their children hanging out with the rough crowd that frequented the panyards in the early years. Many of the men there engaged in gambling, drinking, carousing, and physical fighting and were generally thought to be a bad element—“badjohns” in Trinidad parlance—who were often in trouble with the law.

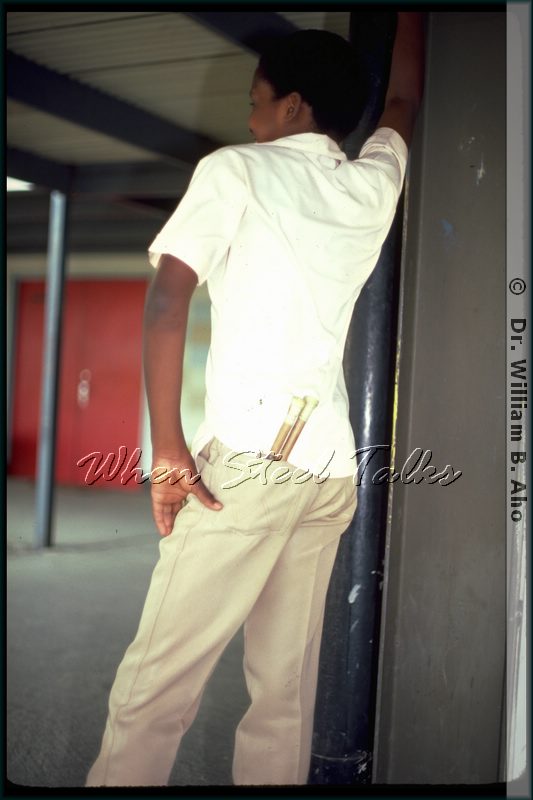

Bertie Marshall

Bertie Marshall

Bertie Marshall,

pan player, tuner, and steel drum innovator, recalled that:

“I didn’t have

to ask my mother’s permission to play pan. I knew her well enough to

know that I would be able to hang around pan and panmen only over her

dead body.” (Marshall, 1972, Vol. 2, No. 1:8). He recalled also that

teachers would warn students about hanging around the panmen, but the

panyard was on the path he took to and from school and he could hear the

sounds of the panyard from his schoolroom. “So, in spite of everything

we hung around and I came to know Spree (Simon) …and others.” (ibid.,

No. 2:3)

The opinions and observations cited above seem to represent the dominant middle-class view of steelbands today in Trinidad. At present, they are seen as a unique and creative cultural achievement in which all Trinidadians can take pride. This view evolved due to several factors to be discussed later. Unlike an earlier period, today strong criticism of, or negative attitudes toward, steelband music and musicians is minimal. Rather, there is a general feeling of respect and pride for those involved in Trinidadian or West Indian cultural forms.

Violence in the Steelband Movement

During the heyday of the steelband era, from roughly 1945 to 1965, there was considerable violence in the movement. There was violence between bands and between bands and the police. It is generally accepted that the police-steelbands conflict was related to the noise the bands made, parading on the streets without a permit, stealing dustbins and other items to use as instruments, and the steeldrum’s lack of acceptance by the government, ruling classes, and police as a legitimate musical instrument. Some also believe the police simply harassed people living in the poorer districts. Inter-band rivalry was related to territoriality, arguments over girl friends, accusations of theft of each others’ tunes, over-enthusiastic followers and supporters, or even accident, when, for instance, a bottle was thrown by someone unrelated to either band. The 1952 report of the government steelbands committee, known as the Canon Farquhar Committee, is instructive in this regard:

“The steelband is essentially a creation of the masses with their poor housing, overcrowding, unemployment, large families and general lack of opportunity for recreation and cultural expression. It was as if in unconscious protest of these delimiting circumstances that underprivileged youth evolved a medium of self-expression which seems destined to make a distinctive contribution to the cultural life of the West Indies.

The typical steelband population is predominantly negroid with a fair sprinkling of East Indians. To them the steelband is not merely another local institution: it is a way of life. Its devotees have their peculiar mode of dress, manner of speech, style of walking and dancing and, though yet in rudimentary form, group codes and norms of their own. Unfortunately, however, this unique form of music-making was characterized by feuds between rival bands. These clashes were invariably instigated by and centered around the young women of ill repute who followed the bands. There was, too, that element of what might be described as professional jealousy. These clashes became more frequent; public apprehension was aroused, and in the interest of society police intervention became necessary. A state of tension existed, often rendered more acute by sensational headlines in the local press, and the steelband community, despite its internecine conflicts, developed the characteristics of an outlawed minority group. The movement became a menace; clashes developed into pitched battles in which weapons ranging from sticks, stones and bottles to scribers, knives and cutlasses were brought to bear with an alarming disregard for human life and property. There were two fatal woundings. Public apprehension gave way to fear. Police action became more decisive, though at times positively unimaginative, and whole bands and even individual members were restricted to rigidly proscribed areas.” (Farquhar, 1952:2-3)

According to Albert Gomes, instruments were seized, players roughed up, slums invaded, and players frog-marched to prison cells (1974:99). Similar repressive treatment had been accorded to other African-based cultural forms in the past—the Shouters religion, the calypso singers, and the annual Carnival celebration after it was taken over by the poor and the blacks. Earl Lovelace nicely captured the spirit of this era when he wrote that:

“…those were the days when every district around Port of Spain was its own island, and the steelband within its boundaries was its army, providing warriors to uphold it sovereignty. Those were the war days, when every street corner was a garrison; and to be safe, if you came from Belmont, you didn’t let night catch you in St. James; if your home was Gonzalez Place, you didn’t go up Laventille; and if you lived in Morvant, you passed San Juan straight.” (1979:54)

The Trinidadian calypso singer

The Mighty Sparrow sang a

calypso entitled Outcast about how the steelbandsmen were treated:

For a long time to associate yourself wid dem

Was a big crime

If you’ sister talk to a steelband man

De family want to break she hand

Put she out

Lick every teet’ out she mout’

Pass, you a outcast.

(Warner, 1982:86)

Other sections of Paul Keens-Douglas’ previously-quoted

Sugar George illustrate the defensive side of steelband clashes and the concern of panmen for their

instruments:

An’ in those years when pan meant fight, Sugar learn to

fight.

There was no one to pull ah blade

As fast as Sugar George;

He cut an’ he get cut too

But people respect Sugar,

For he only fight when he had to

An’ only because he had to.

But Sugar never forget he pan,

Dey say when fight start an’ band clash,

Sugar take care of he pan first.

Like ah baby he used to wrap it up an’ hide it,

Sometimes in ah canal, sometimes in de bush;

An’ woe to de man who touch

De pan of Sugar George.

(Keens-Douglas, 1979:35-36)

Errol Hill recalls the incessant noisy practicing, often at

times when people wanted peace and quiet. The

noise carried a considerable distance, so people did not

want pan beating in towns, but up in the hills

somewhere. Thus, the police restricted the beating to

specific hours (1983:3). Further, recalls Hill:

“We always jumped up behind these bands on Carnival Day …and

I have been in several …where a rival

band is coming and they’re actually in a no-man’s land and

you can feel the tension in the band as they

came closer and closer and closer but no one would leave. On

one occasion the bands actually crossed each

other on the same street, and you could just feel them going

and everybody’s looking and the eyes come out

all over your head, looking around to see what’s gonna

happen. Occasionally at that time someone would

throw a bottle and that was the last thing you’d want to

happen because it would immediately be felt that

it’s coming from one of the enemy and all hell would break

loose.” (ibid.)

The roots of some of the steelband territorial rivalry may

well go back to earlier times. According to

Ralph Araujo:

“In those days, the days of the Great Depression, youth in

Belmont was generally touched with poverty but

not unhappy, full of rivalry but not of factional

bitterness. Belmont was the center of our lives. Woodbrook

was a place where we had to change tramcars... it lay in a

direction in which our elder brothers sometimes

sallied forth on their bicycles in pursuit of new

girlfriends—and it is interesting how many marriages

resulted in cross-breeding of the Woodbrook and Belmont

strains. It was a standing joke…that Belmont

boys never married Belmont girls—as we told the girls, they

were too “own way.” This Montague/Capulet

arrangement seems to have created a certain amount of

friendly rivalry between Woodbrook and Newtown

boys on the one hand and Belmont boys on the other, a

rivalry which sometimes surfaces now amongst

those who grew up in that era.” (1984:5)

George Goddard, old-time panman and early president of the Trinidad Steelband Association, also claims

that “Turf clashes preceded the development of steelbands and underprivileged youths would have fought

among themselves or with the police in any event.” (1983:7). In the eulogy delivered for Wilfred “Speaker”

Harrison, early leader of the Desperadoes steelband, he was remembered as having:

“...insisted that the early Despers all have tattoos on their backs, chests or forearms, which was to indicate

Life Membership, and be given code names. He was referred to as The Dresden, and on the battlefield as

Sergeant Rollock and sometimes Inspector Fugot, becoming General in charge of Central Intelligence,

Despers. He organized battle practice sessions…for all the men he would select to operate with him in

launching attacks on the enemy.”

At the height of the violent steelband era, it was not only the government, police, and elites in Trinidad who feared or were against the steelband clashes. A calypso of the time advised the government to “…give the hooligans the old time cat-o-nine and they bound to change their mind. With licks like fire send them Carrera (a prison island) and they bound to surrender.” (DeLeon, 1983:5).

Old-time panman

Carleton Constantine, popularly known as Zigili, recalls

that:

“So much different things used to cause them. A woman from

one band, she have a man from one band and

probably see a next guy from a next band. That is one of the

factors. Then…sometimes …like tunes bands

playing—this band playing this tune say the next one take

their tune. In a dance where drinks is concerned—

anything, anything at all, because that was a era that

violence was very high. So anything could

start a fight.” (1983:4)

Concerning the weapons used in clashes, Tony Slater states that, “Bottles (were used), one or two people

may have a gun …a lot of people get damaged, a lot of instruments get damaged; ‘67 was the worst, it was

a total wreck. All amplification, everything mash up. It was a form of jealousy.” (1983:8).

Curtis Pierre

offers a chilling account of his personal experience in a 1953 steelband clash:

“There was a certain amount of turf rivalry, which there is in any type of group activity. For no other reason

than, you know, you just want to be King of the Rock and guys said, ‘You’re from Belmont and you should

not be walking in Woodbrook.’ It had nothing to do with the quality of your music, it had nothing to do with

whether you had their girl, people have advanced all kinds of reasons, that, you know, this girl was seen

walking with a guy from Invaders so that the boy from Desperadoes got annoyed. My experience in 1953

when steelbands were asked to come on the road for the coronation of Elizabeth when she was crowned;

we had a clash with a band called Ebonites. It was not anything that they knew who we were or we knew

who they were. Some little incident sparked it off and it got real messy. You know, guys were swinging

baseball bats. I got hit with a baseball bat. Lucky nobody was holding it at the time, somebody just flung it

across. One guy next to me got his cheek cut open with a razor. That was the scariest part, you just saw the

flesh part and you saw the teeth and a couple minutes after, the blood. One guy came charging at me with

what looked like a piece of a kitchen fork, a large kitchen fork, and all I could do was raise the tenor pan I

had and hit him across the bridge of his nose and that I remember also seeing the bone just go white and the

guy’s eyes closed and he flaked out and I disappeared. But it was not a pitched, prolonged battle. Within

minutes there were sirens and everybody scattered. Nor were there any sort of vindictive feelings in that

particular battle.” (1983:5)

Pat Chu-Foon

Pat Chu-FoonWorld War II saw several U.S. military bases in Trinidad, and

many movies with violent war, gangster,

and Western themes. The steelbands took on some of the

films’ names, individual steelbandsmen took

actors’ names for their nicknames and emulated actors’

behavior. There are still steelbands bearing some of

these movie-inspired names. Pat Chu-Foon recalls that:

“…those were the days when we used to see a lot of these

films with Back to Bataan and Robert Taylor and Audie Murphy. It inspire the moviegoer and these poor fellas,

some of them just lived in the cinema in

those days. Most of them didn’t work, other than playing

pan, tuning pan, lazing around playing a game of wappie (a card game), they just scrunt for some money to go

to the next matinee and after seeing a good

war picture they want to do the same thing, and this is what

caused a lot of thing, with the steelband

clashing those periods. It was like a game. You would see fellas go up and say, ‘Look, we going up to beat

Casablanca tonight. Invaders, we going and beat the

Invaders.’ You hear how the names are, all war names. Invaders from Woodbrook coming up to clash with so and so

and they meet on this corner. Men used to

walk with razors in their waist.” (1983:4-5).

The steelband badjohn role was an important one, a source of identity for many young Trinidadian males that had to be maintained, even if only as a front. Bertie Marshall reports, “I cultivated my badjohn image. But my badjohnism was a pose really. Still, it was necessary to cultivate the image. And I managed to do this yet at the same time keeping my hands clean—except for a couple of gambling cases which were no big thing, really. But the image was an important thing in those days.” (Marshall, 1972: Vol. 2, No. 5:9).

Positive Influences of the Steelband Movement

Not all of the experiences of the steelband movement were negative. There are success stories on all levels. As Carleton Constantine (Zigili) said in 1983:

“I have to be very grateful to steelband. Because I left this country in 1956 ... and lived in the UK and up to this day I am making a living from steelband. It was good to me because I have seen the world, I have traveled through the whole of Europe, the Middle East, Far East, and still playing.” (1983:5)

Steelband music provided many young Trinidadian males with opportunities for personal growth and the development of leadership skills that they found useful in other areas of their lives.

Curtis Pierre, in response to an open-ended query about steelband, said that:

“A lot of the distance I’ve covered in my life both in terms of a businessman, as a father, as an organizer, I can safely say that the experience I’ve gained, I owe it completely to my exposure in the steelband world. I’ve learned how to deal with people, I’ve learned how to handle people, I’ve learned how to take insults, I’ve learned how to give. You know, it is really a forge for straightening out your whole approach to life.” (1983:10)

George Yeates reports on a perhaps unforeseen outcome of the police-band violence of the early steelband era:

“I had been able to command a great respect among steelbandsmen, and I had that disturbance (a steelband clash) quelled. I did as much work or perhaps even more work than the police, because most of the time the police would come and call me and ask me to go with them whenever they had any steelband clashes. Superintendent Barnes would always come and call me to go speak to both sides because when it came to Despers, and I held the reins of Despers, I would try to keep them out of any further clashes and let them know that those who want to fight cannot be in the band that I run because I am thinking in preparing the band for the music festival and improving the arts, improving the instrument, and these steelband clashes is interfering with my works.” (1983:5-6)

Social Change and Acceptance of Steelbands

A precise ordering of the factors that influenced the gradual acceptance of steelband music is not possible, since they overlapped and since there is no consensus even among persons on the scene, concerning the chronology of events and their importance. Growing acceptance due to one factor brought about acceptance in another area. The factors contributing to steelbands’ greater acceptance include the following:

-

Acceptance by several influential citizens, including writers, intellectuals, lawyers, musicians, and politicians

-

Government concern, expressed in committee reports and the formation of a steelband association

-

Commercial sponsorship

-

Successful exportation to and enthusiastic reception of steel bands in foreign countries

-

Open support from the People’s National Movement political party

-

Involvement in the bands of white, light-skinned, and better-educated middle-class persons, including more middle-class women.

-

Refinements in the instruments

-

The playing of semi-classical and classical music

-

Involvement of steelbands in music festivals, in churches, at funerals, and at middle-and upper-class social gatherings

-

A resurgence of Black Power and pride in the early 1970s

Support of Influential Citizens

Starting in about 1946, the Trinidad Youth Council and its members, including attorney and musician Lenox Pierre, Canon Farquhar, Kelvin Scoon, and Errol Hill, made consistent efforts to gain social acceptance of steelband music, instruments, players, and supporters. Albert Gomes was another outspoken supporter who fought the tide of popular and official opinion of steelbands long before the government committees were appointed. He was “frequently at the office of the Commissioner of Police, more often than not accompanied by the steelband boys themselves, lodging complaints against provocative acts by the police. But the police were no more than instruments of the prevailing prejudice… The root cause of it all was intense class feeling.” (Gomes, 1974:99).

Beryl McBurnie

Beryl McBurnieAt a 1945 meeting of the Legislative Council, to which he had just been elected, Gomes said, “Some people feel that some others should never enjoy themselves …and that the music should belong to one particular class… Personally, while I sit and enjoy Beethoven, it does not blind me to the fact that we have got to live among a people …of diverse races and creeds, and that we cannot fit these in a particular design.” (ibid.)

Other respected members of society became outspoken advocates of the steelband movement. Beryl McBurnie, dancer, choreographer, and founder of the Little Carib Theatre, brought the Invaders steelband into her theater for a performance in 1948 and also got a number of middle-class young men and women involved in steelband.

Government Concern, Recommendations, and Action

The

1952 Farquhar Committee report noted that: “…the government appointed a

committee in November of 1949 to investigate the implications of the (steelband)

problem and in April of 1950 the steelbands themselves organized a

representative body known as the Trinidad and Tobago Steel Bands

Association… With the setting up of machinery for negotiating with the

Steel Bands public reaction became more sympathetic, and a new

psychological approach to the problem gradually became evident. The

steel percussion orchestra, as the steelband is now known, is no longer

regarded as an outlawed nuisance. These orchestras perform at social

clubs, hotels, concerts and dances and, in many instances, have almost

replaced the traditional orchestra. It is hopefully significant too, to

observe the formation of steel orchestras among middle-class youth of

both sexes.” (Farquhar, 1952:5).

A major concern of the committee was

expressed in its findings:

“The cohesion and unity inherent in the steelband movement constitute a great social force which should be

exploited and directed into constructive channels. The steelband

movement is a people’s movement. It has captured the imagination and

energies of the youth of our masses, and provides a ready-made entity

around which a whole system of educational activities and recreational

interests can be advantageously organized. The steelband movement and

the problems which stem from it must he viewed as an integral part of

the general pattern of social and economic life peculiar to the masses

of the colony. In this context one underlying conclusion emerges: there

is imperative need for an awakening of a national sense of community

responsibility.” (ibid.: n.p.)

Although the 1965 interim report of

another government-appointed steelband committee found some fault with

the Steelband Association’s leadership and cooperation, it could observe

that:

“…the Steelbandsmen feel that they have improved the social

situation in respect of gang warfare and that the Association (which was

formed partly for that purpose) and the National Steelband have improved

the situation in respect of inter-band relationships. The Police are

also satisfied that the steelbands as such pose no problem to the peace

and order of society.” (Interim Report, 1965:9)

The same report recommended “continuing most vigorously the struggle for social acceptance of the Steelband Movement at home and acceptance and recognition of the movement abroad.”

Sponsorship

Commercial sponsorship of the bands was another, to some a dubious,

advantage, carrying with it some control over the bands and less

independence than they had previously enjoyed. Nevertheless, the bands

needed the legitimacy, status, funding, and perhaps organization that

sponsorship could provide. Oil companies, banks, airlines, and similar

large enterprises sponsored steel bands starting in the 1950s. They

supplied uniforms emblazoned with their names, as were the drums

themselves, and the sponsors enjoyed good publicity and public relations

benefits. They sometimes sent the bands to other islands or to Europe,

Canada, or the United States. Recalling his early association with the

West Indian Tobacco Company as the sponsor of his Desperadoes steelband,

George Yeates said that:

“From then onwards, this is where I can say

that Despers has been the trendsetters…for good behavior in the

steelband movement, because they no longer had cause to fight…they were

thinking that they would lose their sponsorship, so that sort of held

them.” (1983:7)

Other panmen expressed their views on the role of

sponsorship in the steelband movement. Curtis Pierre thought:

“It was a good thing because even though we all know

it came from the underprivileged, when this thing started to evolve and

the costs started to go up, the bands who had a sponsor …you found that

those bands were better. And then the sponsorship thing got very, very

big and the government got onto it and decided, ‘Okay, well this would

be a nice vote-catching gimmick if we can tell the steelbandsmen that we

are giving instructions to the business community to sponsor their

bands.’ So from a devious motive came a very good end result. It went

out of control in the last couple years where sponsors were being called

upon to pay some thing like twenty or thirty thousand dollars a year for

a band.” (1983:4)

Panmaker and tuner Tony Slater believes that:

“Sponsorships play a good part (in easing the tension). To me it give

and it takes. Because some people say you lost your name, but you get

money. And a lot of bands need money because preparing a band for

Panorama (a Carnival steelband competition) is expensive. Sponsors

have done a lot. They needed money to progress and sponsorship assisted

a lot of bands to progress. Some bands don’t need sponsors, they get

along somehow. But the bands with sponsors, those are the progressive

bands today.” (1963:8).

Pat Chu-Foon’s opinion of sponsorship throws a

new light on the issue:

“Well, long after when they settle down properly and

they were like gentlemen of pan, and pan started to make history in

Europe, then and only then certain top companies started to assist to

choose sponsorships here and there.” (1983:12)

Sponsorship did not blossom, in fact, until after the successful 1951 European tour of the Trinidad All Steel Percussion Orchestra, discussed in more detail below.

The Steelband Abroad

Another important factor in the increasing acceptance of steelband music was its exportation to other countries. In 1951, under the sponsorship of the Trinidad Youth Council, an all-star steelband, called the

Trinidad All Steel Percussion Orchestra (TASPO) was sent to England to play at the Festival of Britain, and to France. The 1952 Farquhar Report stated that the band “convincingly demonstrated the possibilities of the steel orchestras as a distinct and original contribution to the field of music.” (1952:n.p.).

Errol Hill has observed that:

“They were very successful, and once the pan became recognized as a new kind of musical form in England, then the local population had to accept it. Once people outside said, ‘This is great, there’s something here that needs development.’” (1983:5)

Led by police lieutenant Joseph Griffith, the band amazed the European audiences. A London correspondent wrote:

“People smiled indulgently as the rusty pans were rolled off the cart and set up. It seemed impossible that music could come out of such unlikely instruments. But jaws dropped and eyes widened as the first sweet notes were struck and the band swung into

Mambojambo. Feet were soon tapping to the rhythm of the music.” (Hill, 1972:51)

The music critic of the Manchester Guardian found the band’s playing of Toselli’s Serenade “equal to anything that a first-class band could offer. The playing is wonderfully skilled.” (ibid. :51)

Today there are steelbands in many countries outside Trinidad. There is a U.S. Navy steelband organized with the help of Trinidadian Ellie Mannette and steelbands in Boston, New York, Washington-Baltimore, Montreal, Toronto, and in high schools, colleges, and universities throughout the United States, thanks largely to Mannette, now living in the United States, and other Trinidadian promoters. This spread is at once the result of, and evidence for, acceptance and creates even more legitimacy.

Support by the People’s National Movement Party (PNM)

Errol Hill reports that:

“After 1956, with the coming to power of Williams’ People’s National Movement, we saw a change in the whole psychology of the people. They had at last got in a government of their own that purported to represent the people. They were moving toward self-government. It was necessary to establish an indigenous culture, and there was a great surge forward to find those elements of our culture that could be identified as belonging to Trinidad and Tobago. The calypso was one, the steelband was another. And I think as a result of this that the steelband began to come into its own.” (1983:8-9)

J. D. Elder supports this view:

“The sickening picture has undergone radical transformation. The most obvious change in the carnival calypso-steelband movement is the demonstration, at State level, of the admission that Trinidad popular music and musical festivals are elements of a high order in the national culture and that government has responsibility to so recognize it and give tangible demonstration of this attitude. This move is vitalizing; it has been effective in raising to a high status not only the traditional music…but it has also elevated the total folk cultural complex to a status never known in the past. Folklore in all its forms has suddenly attained an attractive status. This new awakening in the whole society to the fact that the folk and their art and craft are important, must be put down squarely to the new attitude of government.” (1968:25-26).

Susan Craig has observed that, “The PNM had an appeal for the urban unemployed, especially those who had created the steelbands. Steel bandsmen became the unofficial ‘army’ of the PNM in 1956.” (1982:391). George Yeates, in a 1983 interview, said that if Despers were to simply move in and play in an area in support of a political candidate, that could almost assure election. They could do this even without a police permit to play. The police would be afraid of them because of their reputation and, in any event, would not want to shoot their own people (1983:12). Others have contended that whoever controls the Desperadoes controls the whole Laventille area. And the band has always supported the PNM. Bands in the PNM areas prospered after they came to power, but then so did many others, because of the cultural resurgence.

Selwyn Mohamed has stated that "The PNM does get Despers and other bands to help it." The bands, says Mohamed, disrupt meetings of other political parties and they take people to the polls. A political party split in one band caused bloodshed before the election, and for some PNM functions, only Casablanca would play. (1985:2)

In 1956 Bertie Marshall formed a small band he named the PNM Band, because they played at everything the PNM had in Laventille. The PNM office was near their practice yard, and although the PNM officials always praised the band and promised to help them, “I have never gotten any of the things promised me by members of government over the last fifteen or sixteen years. Still, we played as the PNM Band.” (Marshall, Vol. 2, No. 4:4).

Although the evidence is mixed concerning the precise role the government, ruling party, and bands play with respect to each other, Curtis Pierre points out that, clearly, the steelbandsmen constitute a potentially valuable voting bloc:

“You would look at the number of bands and they are made up of fifty guys each, and each one of those guys has a spin-off factor of 4.3 or something like that in his family. If you get hold of some of those bands and you multiply by forty and then multiply by five, you have a sizable voting population.” (1983:4-5)

Personal Involvement of the Middle Class

Curtis Pierre

The acceptance of steelbands grew when middle-class, lighter-skinned, and white young people started getting involved, often over the strenuous objections of their parents, teachers, friends, and relatives.

Curtis Pierre became involved in 1949:

“I took the instrument home and I got enough flak from my parents, ‘What the hell you doing with this thing here? I don’t care who plays that. This is the underprivileged.’” (1983:1).

“The grouping in my band would be considered a little above middle class, which was anathema, that kind of thing was just not done by people in that class.” (ibid. :2).

Pierre attributes to his group the change in the degree to which steelbandsmen and women are accepted in society:

“We have been told it’s because of our group…that… ‘You fellas made a breakthrough. You guys don’t realize what you did. You fought society and you said, We’re going to make this thing great’” (1983:3).

Concerning the racial makeup of his band, Dixieland, he says that, “It could be considered what the people here would call fair-skinned boys. And there was not a predominance of Negroes in it at all, mainly because that was what middle class meant in those days. And that’s true, middle class had a certain color. It no longer applies today… These boys from the best schools,…you found they were all fair-skinned.” (ibid. :6).

Teacher, pan player, and arranger

Ray Holman recalls that:

Ray Holman

“The change came about when people like myself, who might have the benefit of a secondary school education, began to come into the bands. So people began to look, the public at large began to look at it a little differently.” (1983:3). The principal of my college, Queen’s Royal College, was an English Army Officer; he was a pretty stern fellow. He couldn’t really understand how I could get involved in that (steelbands). It was like a social outcast at the time.” (ibid. :6).

The band he joined at age thirteen, the Oval

Invaders, accepted him easily:

“They were very glad to have us. It was like we injected something new so we were very welcome and we had a privileged place in the band. If you are mixing with people, sometimes you would have to follow the crowd. But following the crowd for me didn’t mean getting involved in violence. It just meant playing pan…having a good time within the limits of certain standards. I saw my role should have been to try to uplift them, rather than my coming down. This is how I saw it.” (ibid.:7-8).

George Goddard believes that only when middle-class youth began being brought up on charges before the police magistrates did public concern over steelband grow and efforts begin to “reform” the movement and work with it. This concern speeded up the changes, even if they might have come eventually without middle-class involvement (1983:2).

The 1965 Interim Report of the Committee on the Role of Steelband in National Life reported that much of the struggle for social acceptance has been fought by persons outside of the groups from which the original steelbands sprang:

“The efforts…of Dixieland (a group of the St. Mary’s pupils which contained many persons of largely European descent) which persisted in the early 1950s despite some disapproval by some persons closely connected to its members, and

Girl Pat (an all-female steelband of teachers, civil servants, etc.) of the early 1950s. Now we find that there is an appreciable number of ex-Secondary School pupils in the Steelband Movement and the movement has enjoyed such confidence of the Community that it has been upwardly socially mobile to the extent that it embraces many persons who would be classified in our society as middle class. Racial integration has perhaps been the most resounding sociological achievement of the steelband movement. Born in circumstances rather confined to one ethnic group—the Negro—it has spread to every ethnic group in society…We have come across no bands whose rules relating to recruitment would restrict admission of any sector of the population…The steelband movement has made a most significant contribution to the integration of the races.” (1965:10)

Changes in the Repertoire and Instruments

Steelbands were more accepted when the instruments became more refined and melodious, when bands started playing more difficult classical and semi-classical music, and as they performed at local and foreign music festivals and competitions, in churches, at weddings, and at middle and upper class social gatherings. Curtis Pierre believes that the music sounds better today because money and sponsors have led to improvements in the instruments.

“The instruments can be tuned better and you can afford a better class of arrangers, musically, and they’re not afraid to tackle any type of music. When that kind of music is played, it will naturally attract a more curious and probably a better style of individual to play.” (1983:8-9).

Kelvin Scoon, Trinidadian businessman, steelband supporter, calypso judge, and former Secretary of the Youth Council, contends that panmen themselves wanted to learn to play the classics in order to use more notes, to challenge and stretch the range of their instruments and their own abilities, not to please others or to be more accepted by them. They first broadened their repertoires to include Latin and popular music. (1985:2)

Musician, conductor, and arranger Pat Bishop points out that at first the playing of classical music, religious music, hymns, or Christmas carols was met with revulsion by the upper classes. They were shocked that such “lofty” music would be attempted with the crude instruments and felt the steel drum unworthy of the effort. But the pan players persisted and gradually their music was accepted. (1985:2).

According to Scoon, compared to the early days of the steeldrum, the sound of today’s instruments is far more refined, mellower in tone, and there is a much wider range of pitches utilized. Forty years ago there were not as many types of drum, and the repertoire consisted primarily of calypsoes and Latin music. Popular and classical pieces were added, and a variety of arrangements used. Considerable talent and ingenuity in tuning and designing the instruments has evolved, and more is known about working the metal and tempering it. The drumsticks are now rubber-tipped, creating a mellower tone. Influences from jazz and fusion and constantly evolving experimental arrangements characterize the present repertoire. (1985:1)

Although there is no empirical evidence to verify the observation, it seems quite likely that as the steelbands began to engage in sponsored musical competitions with audiences including middle-class people, they sought to maintain and increase the latter’s interest and support by striving for a smoother, more refined sound, a wider range of notes, and a broader repertoire. They were also motivated by their own inner desire to stretch their talents and the potential of their instruments by taking on more challenging musical scores and showing themselves, their fellow countrymen, and the world what could be achieved with talent, hard work, and an instrument of humble origins. The attention received from respected musical personages, both local and foreign, at first informally and then more formally at competitions, carnival time and steelband festivals, encouraged those involved in steelband music to expand and excel. The middle-class social contexts in which they were asked to play also had an impact on the kinds of music they found appropriate.

Participation In Music Competitions

In 1952 steelbands were

invited to participate in the prestigious biennial music festival in

Trinidad and foreign music adjudicators judged their performances. One

of these, Dr. Sydney Northcote from England, at first quite skeptical

about steel bands, eventually came to hail the musicians “Truly

astonishing.” In 1956 he commented that “Their performance was

orchestral in every way. The melodic line was beautifully smooth, almost

like the playing of a string orchestra. The technical skill of it all

proved that there are possibilities of acquiring with the steelband an

orchestral precision.” (Hill, 1972:52)

The enthusiastic reception of steelbands by the U.S. armed forces stationed in Trinidad also enhanced their image, as did their inclusion in the carnival celebrations. Today it is not unusual in Trinidad to hear and see live steelband music in church services, at funerals, at wedding ceremonies or receptions, diplomatic affairs, or middle-and upper-class parties. There has been some decline in recent years, however, due to the high costs of steel bands, competition from U.S. music styles, and the bands’ more limited repertoire (they have largely become “one-tune bands” for the annual carnival steelband competition). Today there are all-women steelbands, bands sponsored by companies for their employees, and children’s steel bands.

Summary and Analysis of Factors of Social Change

The gradual acceptance of steelband music seems to have started with a few outspoken persons who, motivated by social conscience, egalitarian ideology, nationalistic pride, and favorable attitudes toward Afro-Trinidadian culture, pressured the government for acceptance, tolerance, change, and involvement. Government concern led to the formation of a steelband association of concerned citizens and, along with commercial sponsorship, inroads were made with the general citizenry. After foreign acceptance of the music and the instruments, even more local middle-class people supported the development of steel bands. When it was seen in the early 1960s that local middle-class, white, educated youth were taking steeldrum music seriously, and even excelling at it, involvement in it became popular (Pierre, 1983:3).

Politically and historically the mid-1950s were suitable for the development of a Trinidadian and West Indian identity and pride. Great Britain was granting independence to its colonies. Local political leaders needed and wanted the support of the masses and would not have been wise to oppose a form of musical and cultural expression that was so vital to their identity. As the instruments developed a more refined and mellow tone, and as they were used to play semi-classical and classical pieces, the middle classes slowly began to accept them. Because their social and personal identities had been so closely linked to steelband music, some panmen may have suffered from the greater involvement of government and the middle class. Generally though, because of greater involvement in formal education and in the labor market, Trinidadians were upwardly mobile during the era of the rise of the steel bands, and they developed alternate and supplemental social roles and identities (Scoon, 1985:1). Most bands seem to have benefited from the involvement of the middle classes because sponsorship and support allowed them to hire expensive arrangers and tuners, as well as to purchase quality instruments and uniforms, and at times to travel abroad. This is a question on which opinions differ, however.

Recent Developments

Steelbands have undergone considerable change. Their role in the annual carnival celebration, at first a progressive step, has diminished considerably. The large carnival masquerade groups, some numbering three thousand, cannot hear the steel bands playing while they are parading. The steelbands do not want to use amplification, and their method of moving on the streets, with somewhat clumsy racks or stands, seems to hinder their effectiveness at carnival. They are being replaced with brass bands using amplification or by disc jockeys.

Panorama, the steelband competition at carnival, has caused bands to focus on one tune they can perform very well, so they reduce their

repertoire for fêtes and other social events. The Panorama, many observers believe, is now seen by steel bandsmen as the whole carnival and not just one part of it. Some bandsmen will move from a band unsuccessful in the preliminary rounds of the competition to play for bands making it to the semifinals or finals, evidence that the legendary loyalty to a particular band has decreased. Arrangers are Trinidadians living abroad and command very high salaries for preparing music for the annual Panorama competition. Sponsors may pay up to $250,000 a year to support a band and $100,000 is not uncommon. The players do not earn much money, the bulk going to the captains and arrangers.

In 1985 the Black Power-oriented National Joint Action Committee issued a national appeal to fête promoters to hire steelbands rather than disc jockeys to support their national heritage throughout the year (Obika, 1985:1). It is hard to keep bands together throughout the year. Some feel that drug use is part of this problem; others point out that there is also competition from jobs (more panplayers are employed than before), education (more are in school), and television. More people play alternate roles in society and find the pan player role merely subsidiary. Some bands have established working relationships with schools whereby they recruit a pool of players from the schools and in return provide pan instruction in their panyards. Pan seems to reflect less cultural and national pride today. More panmen need and want pay. Curtis Pierre contends that today’s steelbands are too large to be hired for social events such as weddings or fêtes. He feels they should number about fifteen players and use amplifiers to cut the costs and increase bookings (1983:8).

Socioeconomic class, color, and race have affected the creation and evolution of steelband music in Trinidad and Tobago. African customs, including skin drumming, were suppressed by the British colonial government and later by many elite or status-seeking black and colored persons who wished to disassociate themselves from the music, instruments, and life-styles of Trinidad’s poor urban masses of African heritage. Because the instrument and the social organization of the steel bands came to symbolize important, even vital, forms of cultural and racial expression, the poor, urban Afro-Trinidadian steel bandsmen and women persisted in their efforts, refining the instrument and sharpening their own musical talents and skills, expanding their musical repertoire, and eventually winning the support, encouragement, and active assistance of a few key people in Trinidad and abroad. The organization of the bands provided needed social roles for players and opportunities for bandleaders to develop and demonstrate leadership skills and thus fill leadership roles otherwise unavailable to them in the society. Not all of this leadership was channeled into violent conflicts with other bands or the police, and many steelbandsmen have credited their experiences with steelband music with developing skills they have used in work or life in general. Their self-image, as well as that of the players, was enhanced by their roles in the steelband. As the steelbands gained favor both at home and abroad, they were viewed as symbols of individual, racial, community, and national pride and as a unique creative accomplishment. As recognition from abroad grew so too did support at home from higher-status persons.

The several factors that contributed to the gradually increased acceptance of the bands, the players, their instruments, and music indicate that this acceptance was achieved at the expense of the bands’ independence and that it came about only after the musical repertoire had changed, business had exercised some control over the bands’ behavior (lighter-skinned, white, and higher-status people had joined the movement and the government openly supported it.) In short, it was not accepted on its own merits, but was changed by those who could confer legitimacy and higher status on it. Paget Henry, writing on decolonization and neocolonialism, has observed that there is a locally rooted demand for foreign culture, persisting even after decolonization. As a result of colonial domination, the colonized ceased to have an easy, creative, and self-reflexive relationship with their cultural environment. Elements of it had now been systematically imposed from without. (Henry and Stone, 1983:115)

Colonial domination further inhibited the demand for the words, songs, ideas, and other products of the local cultural system. There was a greater demand for foreign cultural products. Decolonization only partially uprooted the set of social and psychological processes that generated the demand for imported culture. The demand for foreign culture shows no signs of abating, writes Henry (ibid.: 116), and the major dynamic in the foreign sector of the cultural system is the institutionalization of a growing American presence (ibid.: 117). This helps explain why many Trinidadian intellectuals, artists, and musicians blame the lack of what they consider sufficient local support for the steelband on the influx of American music and lifestyle in general, which they feel many Trinidadians are adopting too readily, trying to “live like Yankees” at the expense of their own culture’s contributions. Although steelband music has become much more accepted in Trinidad and Tobago and abroad, it still faces competition from foreign musical tastes and difficulties caused by technology, costs, and a lingering and deeply-rooted self-denigration on the part of many Trinidadians.

I am deeply grateful for the invaluable assistance of Anthony and Avril Bryan, Mackie Burnette, Deborah Cabral, Rhode Island College Dean of Arts and Sciences David Greene, Professor Errol Hill of Dartmouth College, Yvonne James of Providence, R.I., and Arima, Trinidad and Tobago, Cynthia Mahabir of Suffolk University, Boston, Ancil McLean, Judith Philip, Everald Philip, Charles Price, Kelvin Scoon, Daniel Segal, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Rhode Island College Faculty Research Committee and the talented and dedicated steelbandsmen and women of Trinidad and Tobago.

-

Anonymous 1, 1985, personal interview, Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago

-

Anonymous 2, 1985, personal interview, Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago

-

Araujo, Ralph, 1984, Memoirs of a Belmont Boy, Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago: Imprint Caribbean Ltd.

-

Bishop, Patricia, 1985, personal interview, Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago

-

Blood, Peter, 1983, People in Carnival , Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago: Imprint Caribbean Ltd.

-

Brereton, Bridget, 1979, Race Relations in Colonial Trinidad, 1870-1900, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

-

Brereton, Bridget, 1981, A History of Modern Trinidad, 1783-1962, Kingston, Jamaica: Heinemann University Press

-

Chu-Foon, Patrick, 1983, personal interview, Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago

-

Constantine, Carleton, 1983, personal interview, Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago

-

Craig, Susan, 1982, Contemporary Caribbean: A Sociological Reader. Vol. 2., Maracas, Trinidad and Tobago, College Press

-

Da Silva, Fabio B., 1984, The Sociology of Music, Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press

-

DeLeon, Rafael, 1983, personal interview, Mt. Lambert, Trinidad and Tobago

-

Elder, J. D., 1968, Social Development of the Traditional Calypso of Trinidad and Tobago, Mimeographed, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago: University of the West Indies

-

Farquhar, M. E., 1952, Report of the Government Steel Bands Committee, Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago

-

Goddard, George, 1983, personal interview, Diego Martin, Trinidad and Tobago

-

Gomes, Albert, 1974, Through a Maze of Colour, Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago: Key Caribbean Publications

-