To Hell and Back to Pan

To Hell and Back to Pan

by Dalton Narine

© 2019 - All Rights Reserved

A When Steel Talks Exclusive

From left, Brooklyn draftees Leroy Barnes, Dalton Narine and the late Kenneth Edwards

Veterans Day Embraces 2 Trinis

who served in Vietnam and elsewhere

It is Veterans Day in the USA, and Gerry Carter and myself relish the moment, the longing for memory of that badass Vietnam War.

Veterans Day is intended to honor and thank all military personnel who served the United States in all wars, particularly living veterans. It is marked by parades and church services and in many places the American flag is hung at half mast.

Veterans Day is officially observed on November 11.

So, it’s the memory of the Vietnam War and how Gerry and I both fought it

as soldiers of the First Infantry Division (The Big Red One).

We were literally drafted together and spent Basic Training in Georgia, along with the late Kenneth Edwards, a St. Mary’s College grad, as well as our buddy, Stephen Phipps, a Paratrooper whose unit jumped into Turkey on the way to Nam and Leroy Barnes.

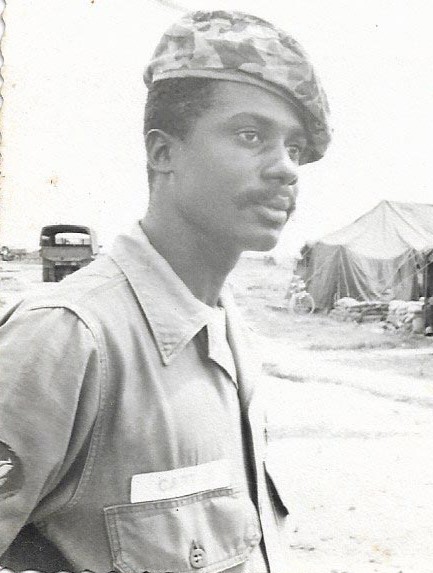

Dalton Narine soon after arriving in Vietnam

It has been 50 years, and only now we reminisce about our experiences. We can jumpstart and even further improve our goal to satisfy readers’ interest in what we have to say about our sprawling commentary on Pan in the early period of the Behind the Bridge story of our experiences prior to our migration to the United States.

Furthermore, about serving in the Military and being in the thick of combat, especially Gerry — a longtime friend — that no movie back in those days could truly articulate the boldness of a country that shoveled so many men; thousands, tens of thousands of troops to verily end the Asian problem.

Vietnam had split into North Vietnam, which was communist, and South Vietnam. If the North Vietnamese communists prevailed, the rest of Southeast Asia would fall like dominoes.

When President John F. Kennedy took office in 1961, he vowed not to allow South Vietnam fall to communism.

It was the era when Gerry and I hung around Duke Street during the glory years of PAN.

I was joined at the hip with Trinidad All Stars, and Gerry found his rhythm with Sputnik, also a Port of Spain band.

Meanwhile, South Vietnam’s conventionally trained army was no match for the Vietcong’s guerrilla-style tactics. In addition, South Vietnam’s Buddhist majority revolted against their president, Ngo Dinh Diem. They saw the Catholic ruler as a tyrant.

The Western-educated Diem, however, wielded absolute power and rose to dictator level in1963. The CIA discussed toppling the regime.

No wonder we both found ourselves entwined in a unit (First Infantry Division) nicknamed The Big Red One, that saw action up and down the famous (and infamous) Iron Triangle, an active organizing center for the Viet Cong, where blood flowed in torrents.

Enter the America solution: The Military draft.

Gerry and I were caught up in the web.

Ho Chi Minh’s North Vietnam (NVA) Viet Cong had already defeated the French,

and now it was America’s turn to turn the tide of the new war, which revealed

the horror of its weaponry.

I was a student at Howard University in the era of Stokely Carmichael, who once suggested that I join his fraternity.

Instead, I accepted an invitation, as a writer, and founded a newsletter featuring Howard’s budding military class that eventually expelled me to the draft board, my having quit the University to enroll at New York University.

In the interim, I received draft orders. The rest is, well, my history.

I gravitated toward the war, despite the average soldier sometimes participating in his own stylish version of humanity, the way, well, Medic Gerald Carter would save, at his own peril, American lives as well as treat South Vietnamese families in their very own Village hell holes.

Gerald H Carter

When The Phantoms of Vietnam Wail too Loudly,

A Battle Hero Escapes To South Florida To Reminisce

And Talk Jazz With Old Friends and Watch

American Football on Sunday afternoon.

“You can pick up the answers through experience and by the very nature of the wounds,” Gerry recalls.

“You have to make snap judgments. And you can’t look back. Now, though, there are days I’d say to myself, `If only I had more time with this guy and that guy, maybe they’d be alive today.’ ”

To some GIs in Vietnam, words from Jimi Hendrix rang true.

“Once you’re dead,” Hendrix had said, “you’re made for life.”

Hendricks was a paratrooper in the Nam. I interviewed him.

Then he scratched the military and, of course, the rest is history. What with his Woodstock rendition of America’s anthem, “Star Spangled Banner” reverberating around the world, to this day.

Now and again, Carter says, some troopers would summon up the courage to die for the sake of their mates, ending thoughts about home and cars, girlfriends and other loved ones.

But others were convinced they’d make it back. One of them, Carter remembers, was Lt. David Heights.

“On the 20-day journey to NAM, we became friends quickly,” Carter recalls. “I can still see us on the deck talking about life. He had such a positive attitude, he was sure he’d make it back to this girl he loved so much. Even the night before it happened, on perimeter duty in An Loc, he was upbeat and talking about what kind of business he’d get into once he got back.”

One night, a day or so preceding an ensuing massacre, I dropped by Gerry’s hootch, nearby. The Lieutenant was in a jovial mood.

We had a good time.

Next afternoon, Heights was commanding a unit of a lengthy convoy of tanks, personnel carriers, jeeps and trucks that snaked from their firebase outside of An Loc, through the village and down a dirt road that led to the bridge at An Loc. Across the way, the jungle hung upon the skirt of a small field that was hemmed in by dense tree line. The soldiers were headed in that direction. The word among the troops was that a North Vietnamese regiment had moved in. The division’s mission was to destroy the encampment.

“They fooled us,” Carter says of the enemy’s predatory guile.

“A bunch of ARVN soldiers [Army, Republic of Vietnam) stacked the bridge,

and we thought that, being our allies, they were in on the mission.

But they were NVA disguised as ARVNs, and we got hit from every possible

angle.”

Carter’s unit couldn’t turn back.

“They destroyed the lead tank and we couldn’t get it off the bridge because of intense fire and mortar rounds coming in from every angle. We lost two-thirds of our men there.”

Indeed, while treating the wounded, Carter found his lieutenant “in pieces.”

The sugarcoated optimism that Carter and the lieutenant had shared suddenly turned rancid, he says. “I finally got a sense about the negativity of war.”

Not long after the Air Force had delivered Armageddon to the North Vietnamese to end the operation, another battle confronted Carter. Another friend was slipping away.

“He was still breathing when I got to him,” Carter says of the infantryman. “But his head looked like a squashed ripe fruit. His brains were oozing from his skull and I kept telling him that he’d be all right. That as soon as the Medevacs [choppers that evacuated the wounded] arrived, he’d be the first one aboard. But I think he knew I wasn’t telling the truth.”

Carter says he had never felt as helpless in all his experiences in the war. And that is one reason Carter won’t visit the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C.

“Too many names and too few answers. How could I deal with that?” he says.

Carter wishes that the nation would honor all war dead, though, because of the ultimate sacrifice they made to the country, political circumstances notwithstanding.

“That’s why we should treat Veterans Day with more solemnity,” he says.

On patrol in Hobo Woods, troops walk past bomb crater in wake of bombing assault on VC

Dalton J Narine

I was trained as an Air Traffic Controller, a lone Black soldier among a class of white Infantry men. It was an 8-month course held at an Air Force Base in Biloxi, Mississippi.

Dalton Narine bringing in aircraft to pummel the Vietcong late afternoon in phuoc Vinh

I graduated at the top of the class. The photo would say it all. The group kneeled for the shot. They pushed me to the front. I don’t think anyone in the group showed off the pic to their friends and family. I mean, we were in redneck country.

Twenty-two days later, on the long trip to NAM, my unit climbed down the ship’s rope ladder, shuffled down a plank, and ogled Vietnamese girls dressed to the nines in their native Ao Dai, a tight-fitting silk tunic worn over trousers.

Before dawn arrived, we received basic information in the hooch, our first orders:

“Grab your M-16 rifle. Designated choppers will be sitting at a makeshift airfield to whisk you straight to an early-morning rescue operation in the jungle.”

I boarded the first chopper. We scrambled out and headed into the bush. My eyes focused on a lone troop roaming the battlefield in a sort of a drunken stupor.

The sun coming up right then and there, brought light into the jungle.

There was nothing we could have done to ease the pain.

Troops from other companies, it seemed, began to pack about 100 dead grunts into green body bags.

The ambushed men had fought desperately, and now, headed to the Beyond, they were laid out like leftover trees in a storm.

I walk up to the only trooper alive. He has a blank, unfocused gaze, emotionally detached from the horrors,

Narine:

“What are you thinking?”

They’re all gone (A thousand-yard stare wells up)

“How did it go?” We went in and … it was an ambush.

I held his hand. It was sappy. His voice sad. “Gone, all gone.”

Jesus Christ, my first day in Nam. I tried to

console a warrior, but he walked away. Heaven knows where to.

I wanted to help pack the body bags, but I couldn’t take it.

Gerald H Carter

“It seemed like we’d just gotten off the ship from San Francisco, and the very next day we were rolling through the jungle in Phu Loi with tanks and armored Personnel carriers (APCs) on a mission to recover a downed pilot. We found the plane but a guy got his leg blown off by a mine when he stepped off an APC to help with the rescue.”

It was Gerry’s first casualty.

Dalton Narine recovers from severe bites by a thousand or so Marabunta ants while on patrol in the Ho Bo Woods.

I’ll never forget that day.

I mean, I was 12 years old, and I cringed in the theatre when I saw those huge marabuntas in The Naked Jungle, Charlton Heston’s flick.

My MOS (Military Occupational Specialty) meant that I was humping all over the map:

I controlled multiple aircraft, particularly helicopters and military jets; as well as roaming the (LZs), deadly landing zones that would enable us to grasp opportunity to ensure the Viet Cong weren’t monitoring our activities, especially at dawn, that is, before our troops would have swooped in on choppers to invade the battlefield.

This morning, my mission would serve to help a short-handed patrol in the deadly Ho Bo Woods, an awesome jungle crabbed with VC. Lots of them.

Well, I was the first to jump into the elephant grass, a fave VC hiding area.

I was met by two Chieu hois (Vietnamese soldiers) who’d direct us through the Woods’ beastly jungle. Now, three of us are walking Point, the infantry hanging on in our wake. One of the Chieus jumps ahead. It is left to me to follow him on the trail. He had me walking, instead, into one of three 18-foot Palm trees. First, he wrapped himself around the palm, then shifted, as if the move was a dodge, and I followed him smack into the second tree.

Suddenly, a hostile pain ran up and down my back, down to my groin, even. Thousands of them, these marabuntas. It was the moment to scream, never mind the enemy might have been within, and could have ambushed us.

Death would be my next pain, I thought. But my front line rushed up, dis-robed me, naked as I was born, then beat the hell out of the buntas knawing at my groin, across the back and jerking my head to a scream that bellowed throughout the blasted jungle.

It took a load of infantry troops taking turns to douse my body with water from their canteens, then wipe the scum off my naked torso.

We rested a ways from the bunta-ridden palms. Took us about a half hour before the trail arrived. We began to hump through the bush, the brothers laughing at me, how much I’ve been indebted to them.

I got up and was about to choke the Chieu Hoi to death.

Madly insane, I was.

I walked point with a trooper who tossed me his rucksack. I threw mine into the bush, canteen and all.

An African American commander leads US troops through the jungle near the iron triangle area. Right after I bumped into a tree full of marabunto

I knew I would be heading back to my unit. But I gritted my teeth and walked point with the lead Chieu Hoi.

I might have sprung deeper into the jungle.

To prove what?

That I can kill a Viet Cong just so, to save embarrassment?

Yeah, I remember well what they did to my buddy, Slick, as we stalked

up a hill and he got hit in the head by a booby-trapped fruit dangling above

a stream. I was a ways behind. The sound was that of a thunder-clap.

I dunno. Could be that further down the hill, Slick had handed me

photographs of his wife and three toddlers. I sat at the foot of a

tree trying to understand my role. I cried.

Gerald H Carter

Gerald H Carter, a medic with The First Infantry Division in the Vietnam War, received the Bronze Star, a combat medic badge with the V device, which denotes heroism, the 4th highest Military decoration for Valor, saving many lives with calm detachment at the risk of his own.

The Infantry was sending up flares to squeeze more light in the jungle.

Gerry came upon a soldier, outside a tank, with a gaping wound.

A mortar round blew up right in front of them. It knocked Gerry back,

and threw the soldier in the air, up in the trees.

When he came down, he was still alive, but in real bad shape. Gerry put him back together, mobilized him, gave him morphine.

Meanwhile, a sergeant was running out of luck at the machine gun atop his burning tank. Carter climbed through the inferno, stretched an arm into the tank’s cupola and grabbed the hand of the machine gunner who was slumped over his weapon.

It came off in Carter’s hand.

From the socket.

Just like that.

Carter was getting to a new area of the soul.

So he shrank away from the flaming tank, blocked out the fresh image and

the awful smell and cared for the scores of wounded well past dawn.

Gen. William Westmoreland helicoptered in to praise the survivors.

“How many have you killed,” he asked them as he walked up and down the ranks.

Carter received the Bronze Star, a combat medic badge with the V device, which denotes heroism, the 4th highest Military decoration for Valor, saving many lives with calm detachment at the risk of his own.

About Lt. Heights: it was here the mission stumbled upon North Vietnamese troops disguised as ARVNs, America’s Vietnamese fighters.

Carter’s The Big Red One (First Infantry Division) was in a bind. They lost their Lieutenant. Just a few nights earlier, Carter, LT and myself were shooting the breeze around midnight outside Carter’s hooch.

Dalton Narine’s unit bunkers down in the Michelin’s Rubber Plantation,

Phuoc Vinh, Vietnam. Viet Cong roamed the area and had lots of

firefights with us. Photo courtesy Dalton Narine

Dalton Narine’s unit bunkers down in the Michelin’s Rubber Plantation,

Phuoc Vinh, Vietnam. Viet Cong roamed the area and had lots of

firefights with us. Photo courtesy Dalton NarineDalton J Narine

Why do Vietnam vets suffer so?

For me, the war will never be in remission. It’s an indelible tattoo

on my mind. I spent eight days in a hospital upon my return home from

the war.

Then they gave me 500 milligrams of Thorazine, an anti-psychotic medication

used to treat psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia or manic-depression.

They had me recuperating at the US Naval Base in Chaguaramas. There, I was fed more Thorazine.

Neville Jules, and Trinidad All Stars resident arranger Leon “Smooth” Edwards relax at the All Stars Pan yard

The Brass gave me a break and I stumbled through Port of Spain, where I reconnected with Neville Jules and Leon “Smooth” Edwards at the Henry Street panyard.

They saved my ass. Jules thought I was a vagrant.

You drunk?

No.

Looks like you on drugs?

Ain’t no dope I ever smoked, you know that, CAP. Never smoked.

Thorazine, courtesy of the Military Base.

Jules:

Get rid of it. Come back to the band (Trinidad All Stars). We’ve

got a few Bomb

songs and a Panorama piece. The Lizard, by

Sparrow.

Dalton Narine with Catelli Trinidad All Stars on Carnival Tuesday on the way to the Savannah

It was the best Panorama time I’ve ever had.

The Lizard, like Jules, pumped me up. I tossed the meds into a canal.

I became “normal” again.

I spent years with Catelli Trinidad All Stars. Still remember the

J’Ouvert Bombs.

They kept me

alive and I danced the Pan all over POS. As lagniappe, Jules assigned

me to a few gigs at the usual Sunday night Do, gig, and later to the stage

side that made its name at The Hilton.

Back to the States

Then I was released as a “baby killer” into a society that didn’t care for

me in its classrooms, workplace or even the Veterans Administration.

My professor: “You know, you got that distant look, as if your mind’s still back there; you ought to take a year off before returning to college.”

My supervisor, in the accounting department of CBS-TV in New York: “What do you mean you can’t stand those machine-gun nests all over the office? Those sounds are typewriters. Were you in Vietnam? Have you been to the VA? You don’t know what the Veterans Administration is?”

Did the VA really try to ease the transition?

The psychiatrist: “My son, you’re suffering from combat fatigue. Here are some pills that’ll help you. But come and see me every six weeks.”

I’d never been high in my life until I took those pills. The euphoria was like sitting on the left hand of God, and I wasn’t accustomed to being there. And so began those little wars the VA and I have been battling over the years. Therapists wanted to hear all, and it was difficult not to stonewall.

But little by little, the mind allowed a peek, flashing back to incidents like the crew chief tutoring me on door-gunner techniques one afternoon and losing his life the next when his Chinook was shot down. Forty infantry-men died during that helicopter troop delivery that went awry. By happenstance, I was assigned to a Huey, a swifter, more agile killing machine. Also coming readily to mind is the scent of weeks-old dirt and human excrement and the thousand-yard stare from cadaverous faces as young men piled on the chopper during troop extractions in War Zone D.

PS:

In time, one morning the brain had stopped. On average, twenty-two Vietnam veterans commit suicide every day, 50 years or so after the War. Look it up. All day, every year.

I’d have made the list that morning, because with the brain scorched, who knows what I might have done.

The brain freezed (my word) again one morning at a Port of Spain hotel.

I’d have been the 22nd veteran to hangout in the hole that day for sure.

I called my psychiatrist back in the States and she warned me to get the hell out of there.

Seven psychiatrists greeted me in ER at the VA hospital.

My mind was in a rut with a Dissociative disorder on the brain. Almost died jumping out to reach Florida. Straight, no chaser.

Oh, I drink only water. The kidneys demand it.

Reminds me of a POS General Hospital doctor who, years ago, took pictures of my kidneys, then joked (did he really?) “A big steel band man like you can’t pass a little kidney stone?”

Ha, Some joke. I dashed to the airport. The following morning a VA doctor performed surgery.

They don’t play with Veterans. Yes, Agent Orange has bedeviled

my kidneys since I came back. But I’m all right now. I stay

to myself.

Gerald H Carter

After we took care of our dead and injured, we went out beyond our perimeter

searching for injured VCs.

And we found this young boy trying to attack us. He was hit many times. What we figured stopped him was a bullet to the head. He wore a bandage on his head, and another on his foot.

At that point, it was then that we came to the realization that the Viet Cong were really determined to fight to the end.

That the bullet stuck in the middle of the VC boy’s forehead tells the story about a war we couldn’t win.

Dalton Narine back home from Viet Nam War. “I became a better man and better writer”

Dalton Narine is a Disabled Vietnam Veteran,

who wrote for the New York Village Voice.

He won writing awards at The Miami Herald, The Village Voice

and Ebony magazine.

Narine currently writes for a California magazine, and is pushing

toward

the final draft of his first screenplay.

Quod erat demonstrandum

Leave a comment in the WST forum

Dalton Narine is a Belmont-born Trinidadian who dabbled in the arts and wrote about Trinidad & Tobago culture. He spent the other half of his career as a filmmaker and TV broadcaster during T&T’s annual Carnival. Narine is an avid collector of calypsos by The Mighty Shadow, a singer, he says, who had a knack for telling stories on himself and his own country that, at last, has embraced him.

contact Dalton Narine at: narain67@gmail.com