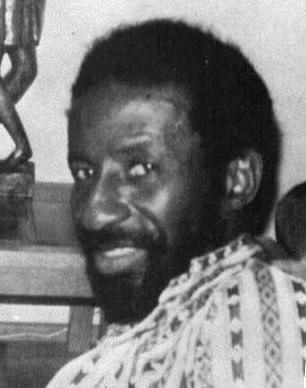

Francis “Patsy” Haynes

October 29 (editor’s note this article was originally published in 1987) will mark two years since we bade farewell to Francis “Patsy” Haynes — a name of which a lot more of us should have been more keenly aware. A lot more of us should have known of his exploits. That Patsy Haynes continued to ply his musical trade right up, practically, to the time of his death in 1985, frequently in a manner not at all commensurate with his creative potency is, if anything, a study in indignity. Patsy Haynes was a hero. Patsy Haynes was a genius. But he was these things because of being, first of all, of the steel band milieu. And there’s the rub.

Elated he was, right from age nine when his love affair with pan music began, to be among the chosen, the anointed—those who would vastly enrich the human experience with a glorious new sound. So his elation at being there manifested itself in the way he gave his all to the pan world and the worlds beyond. And what he got in return, apart from the personal satisfaction of doing what he enjoyed most, was not a helluva lot.

There are of course those who recognized and appreciated the Haynes genius. For starters, there are those who were around and aware in Trinidad back when Patsy’s first-pan prowess around Casablanca Steel Band was legend. His selection in 1951 for the Trinidad All-Steel Percussion Orchestra (TASPO), the first representative Trinidad steel band to bring the pan sound to foreign shores, was a foregone conclusion. There have been countless audiences, in the United States, in Europe— school kids, the high and mighty, average Joe’s—who have listened in wonderment while he displayed his mastery of the instrument, magically and convincingly demonstrating the pans to indeed be a medium of love and caring and understanding.

He meant it as no slight to anyone when he proclaimed the sound of musical steel to be his first love. His loved ones—wife, children, other close family members—did not of course take a back seat to his beloved pans. But then neither did his pans yield pride of place to anyone or anything.

Patsy Haynes did try to be conventional, to be more mainstream. But the need to merely “exist” was simply outmatched by the passion for making music, which totally consumed him. A supervisor at a New York City plaque manufacturing operation where Patsy once worked dared to call one day to inquire about his absence from the job. To which the placid rejoinder from this

troubadour supreme was that he would deal with making plaques only after he was through practicing. Ergo, as of that moment

no more making plaques, only music. With, of course, the inherent risks, humiliations, whatever, attending such conviction.

But what music! The glory years of first-

pan stardom with Casablanca behind him, a “second wind” of enthusiasm came surging through in the 60’s when he became enamored of the then-relatively new double-tenor. He adopted the double-tenor as his very own—as if Bertie Marshall had conceptualized and crafted this handy addition to the instrumental ensemble with him in mind. That deft touch of his could take you literally leaping with him to the outer limits on flights of fantasy. It was also a touch that could convey soothingly, reassuringly:

all is well; it’s OK.

All was not well with Patsy in the last

couple of years prior to his death. He was quite ill. But in the “everything is beautiful” lifestyle that he espoused, illness would not be worn like some red badge of courage. So that his rigid regimen of dialysis treatment for failing kidneys would be mentioned by him, if it had to be, in the most matter-of-fact terms imaginable. And perish the thought that illness interfere with his playing! Patsy Haynes believed the Good Lord set him upon this earth to reach people’s souls with his music, and that’s what he was unshakably determined to do.

What a pity that others well placed to do so could not have reciprocated, in some small measure, the goodwill that oozed so readily from the free spirit that was Patsy Haynes. He did not hold them accountable, though. It was the tenor of his personality to not dwell on such “frivolities.” Making music was important; making folks admit to the cruel dimensions of their apathetic behavior was not.

And so, with no fanfare at all announcing that Patsy Haynes, age 55, would cease to tap out what the Bard of Avon called “sounds and sweet airs that give delight and hurt not,” came time for a goodbye to this giant (short of stature though he ironically was). He will of course remain with us through his music and through the memory of an irrepressible spirit that could radiate sunshine on the darkest of days. To his buddies, he had become partial to being referred to as “the Sheik.” Thus, the Sheik

is dead. Long live the Sheik.

DISCOGRAPHY

The following albums by jazz drummer Beaver Harris all feature

Francis “Patsy” Haynes on steel pans:

-

Beaver Harris, “Ragtime to No Time” (360 Records)

-

Beaver Harris, “In: Sanity” (Black Saint Records)

-

Beaver Harris/Don Pullen, “A Well Kept Secret” (Shemp Records)

-

Beaver Harris, “Necaumongus” (Cadence Records)