England, U.K. - Author James McGrath said to When Steel Talks “I'm especially keen to re-promote this piece at present, because a new, very long book on the Beatles has just been published - and, though it has its merits, it is very disappointing to see that it scarcely mentions Lord Woodbine as a musician, only as a promoter.” - October 17, 2013

------------------------------------------------

Liverpool black history and the Beatles.

James, by now you’ve written several articles about the Beatles, mostly on the songs of John Lennon and Paul McCartney and the way they define and redefine — each in his own way — themes like the passing of time, belonging and isolation and imagined communities. Your dissertation extends your scope to their early surroundings, notably Liverpool’s black community. So our first question is rather obvious...

— How does Liverpool black history tie in with your research on the Beatles?

“My study compares representations of home, class, religion and nation in John Lennon and Paul McCartney’s music and lyrics. In the last year of my research, I managed to find quite a lot of unexpected material concerning a further theme — the black Liverpudlian perspective on the Beatles’ history. Much of this came from my own interviews with various people who remember the young Beatles. I also found several valuable but rarely-mentioned published sources. This topic amounts to around a tenth of my PhD — so about 10,000 words.

“Of course, I come at this from an outside perspective. I’m not black, I’m not from Liverpool, and I wasn’t born when these events took place.

“However, the black Liverpudlian perspectives on the Beatles seem to me to be very important in understanding the group’s musical and cultural roots. Also, a lot of this material has been ignored or dismissed by writers on the Beatles. However, I managed to interview people who recall this from different perspectives within Liverpool’s ethnic population in the period of 1958-1962. Liverpool’s black and mixed-‘race’ community is itself diverse, and some of my interviewees did not know each other. As I’ll explain though, their memories are strikingly concurrent — not just with those of other interviewees, but also with occasional, rarely-quoted comments from John Lennon and Paul McCartney.”

— Can you say a little more about what your research has entailed?

“As a PhD student, it’s been both necessary and a pleasure for me to read or re-read everything I could find about the Beatles-interviews, biographies, studies, and lots of social history. And of course, I’ve also been listening extensively to the work, which again is a pleasure. There’s a general idea that if you’re studying certain musicians’ work, it becomes hard to continue enjoying that music. I’ve found it works the other way. Songs I hadn’t really thought anything of before — “Your Mother Should Know” and “Don’t Let Me Down”, for example — suddenly sounded like the most amazing things the Beatles recorded.

“I’ve loved the Beatles music ever since I was a child, when I first learnt to work a record player and heard “Strawberry Fields Forever”. What prompted me to begin a Cultural Studies PhD though was when, about five years ago, I saw a copy of the Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band LP in the window of a rural junk shop. It just looked utterly right there amongst all the curios and clocks and bits of schlock you get in junk shops. I was tempted to buy it, but that object really seemed to belong there in the junk shop window. I suppose that’s the long way of saying that I’m interested in the Beatles from a social historical viewpoint. And this — gradually — led me to research the black Liverpudlian perspectives on the Beatles’ history.”

— And what can you tell us about these?

“A few years ago Paul McCartney spoke about how the Beatles’ music was influenced by Liverpool’s different ethnic sounds. In particular, he mentioned “calypsos via the Liverpool Caribbean community,” which, he proudly added, “was the oldest in England.” McCartney said that sailors and immigrants made Liverpool a “melting pot” of different ethnic sounds — and he added: “We took what we liked from all that.”1 Now as we know, the Beatles were always keen to use diverse sounds on their records — like the sitar, or avant-garde European influences, and, of course black R&B music. This curiosity they had about different styles of music was first apparent in Liverpool — and as I’ll explain, many of the people they looked to were black musicians.”

— Have you asked McCartney about this?

“No. I’d like to. Before I became aware of the black angle on the Beatles story, I had tried to contact his office, but McCartney is a busy man. He hasn’t often spoken about how Liverpool’s black community influenced the Beatles, but he isn’t often asked about it either. But what I’m really interested in is how people in Liverpool remember this.”

— So what have you found out and how?

“I’ve interviewed people who witnessed and remember the Beatles often hanging out with black musicians, in Liverpool 8/Toxteth especially, between 1958 and 1962. But although my interviews are new, this has been known in Liverpool all along, as some listeners are aware.”

— And, what’s the story with this?

“The first I ever heard about it came from my PhD supervisor, Dr Peter Mills of Leeds Metropolitan University. In the 1980s, Peter was the singer with the Liverpool band Innocents Abroad, and lived in the city for several years. In one of our first tutorials, Peter mentioned something that really fascinated me. He said it was often mentioned in Liverpool that the Beatles had a manager in their early years who, for some reason, had been written out of the history books. I thought he might mean Allan Williams, who worked as the Beatles’ manager before Brian Epstein, but Peter said no, this was someone else — a black gentleman. Peter didn’t know this man’s name, but said that when he was there in the 1980s, this man apparently still lived in Liverpool.

“About four years later, after some unexpected finds with my research — owing to a very significant extent to the kindness of various interviewees — I finally realised who Peter must have meant. Now this mysterious black gentleman, I’ll clarify now, was not — as far as I can tell — the Beatles manager in any contractual sense. However, I realised that from interviewing various people and also from turning up some rarely-cited sources that he was close enough to the Beatles, both professionally and personally, for various people to assume that he was their manager and to remember him that way. His name was Lord Woodbine.”

Photograph taken by Allan Williams’ brother-in-law, Barry Chang, in 1960 at the Arnhem War Memorial in the Netherlands; (left to right) Beatles manager Allan Williams, his wife Beryl, Williams’ business partner and black Calypso singer Lord Woodbine, Stuart Sutcliffe, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Pete Best

— So who was Lord Woodbine?

“He was born Harold Phillips in 1928 in Trinidad. He served in the RAF and then in 1948 arrived in England on HMS Windrush. He settled in Liverpool, where he worked (amongst other things) as a lorry driver, barman, decorator and builder. Now Lord Woodbine is in fact mentioned in several books on the Beatles, but only fleetingly.2 My point here is that these do not come close to doing justice to Woodbine’s importance in Liverpool music, not least, that of the Beatles.

“Lord Woodbine — also known as Woody — was the business partner of Allan Williams, who worked as the Beatles’ manager. Woodbine ran two clubs in Liverpool 8, the Cabaret Artistes’ Social Club and then the New Colony. The Beatles — or the Silver Beetles, then — played at both of these clubs, and for a week or so played live musical accompaniment to a stripper at the Cabaret Artistes Social Club. The young Beatles often socialized and drank with Woodbine, and would sometimes sleep the night at his New Colony Club on Berkeley Street. Woodbine also helped arrange their first Hamburg trip, and went there with them.”

— But there was more to Lord Woodbine than his professional connections with the Beatles, wasn’t there?

“Much more. What’s barely mentioned in the Beatles books is that Lord Woodbine was a gifted musician, and very influential in Britain’s black musical culture.”

— How?

“He started and led one of the very first steelpan orchestras in Britain, the All-Steel Caribbean Band. He was also one of the first calypso singers to perform in Britain, and later, Hamburg. Lord Woodbine, Harold Phillips’ nickname, marked the respect he earned as a singer. Calypso singers are often called ‘Lord’. The ‘Woodbine’ part of his name came from a calypso he wrote about characters named after cigarettes.”

In the tracks of a steelband. As you say and just as the photo above shows, Lord Woodbine accompanied the Beatles to Hamburg. Let’s go into some more detail about this man.

— You say, he was both a singer and songwriter...

“Yes — as were two white youngsters who seemed very intrigued by him. John Lennon and Paul McCartney started writing songs as teenagers. Now in years of reading about the Beatles, I’ve only learnt of one other person they met in Liverpool who was a singer and songwriter. This was Lord Woodbine.”

— Have you found out much about his songs?

“Only bits and pieces. Wes Paul, a respected Liverpool musician, was a close friend of Woodbine. Wes told me about one of Woodbine’s trips to Hamburg in the early 1960s. He often sang his calypsos in the Hamburg clubs, and one night Woodbine decided to unveil a new composition of his called “Hitler Rode Into Berlin On The Back Of A Donkey”. Hitler was a forbidden subject for satire in Germany in the 1960s, and the authorities were not pleased about Woodbine’s new calypso. So they tried to deport him, giving him a plane ticket — which he sold, and used the money to stay in Hamburg for a bit longer.”3

— When did the Beatles first meet him?

“The biographies, including the most detailed ones, imply that the Beatles first met Lord Woodbine when they started playing in his clubs, in 1960. But it was actually earlier, more like 1958. He started noticing John Lennon and Paul McCartney in the audience, following his steelpan group around. Now they probably weren’t the only white boys who went to see the steelband — but Woodbine and others noticed that these two seemed to be there all the time.”

— Where was the steel band playing?

“Various places — but particularly the New Colony, the Joker’s Club, and the Jacaranda.”

— But weren’t John and Paul often in the Jacaranda Bar at night anyway — because it was owned by Allan Williams?

“Yes. But whenever the steel band were playing, John and Paul paid close attention, and this was noticed. It was well-known that these white teenagers had their own band, and there was a feeling amongst the steelpannists that these boys were trying to pick up the black sound.”

— And one of the steelpannists was Gerry Gobin...

“Yes. Candace Smith, or Nora Smith as she was then known, was Gerry Gobin’s partner at the time, this was 1958. Candace has spoken about this before; she described how John and Paul would be there by the stage, overwhelmed by the Caribbean music.”4

— And you’ve spoken to Candace yourself?

“I have. Candace told me how Gerry kept coming back from the steelpan shows and saying: “Those kids were there again.” Initially, Gerry was not impressed by John and Paul — either by their own music, or by how they kept on following the steelband. Sometimes, at the end of the night in the Jacaranda basement, where the steel band would play, John and Paul would make it look like they were helping out by collecting glasses and emptying ash trays. Gerry noticed though, that this seemed to be an excuse for them to get onstage and have a go themselves on the steel drums. It seems that John and Paul were trying to develop a black element to their own sound. Candace summarises: “They wanted to learn rhythm.”5

— But Gerry played a further role in the Beatles’ story, didn’t he?

“He did. By 1960, the All-Steel Caribbean Band had become the Royal Caribbean Steel Band. Lord Woodbine left around that point, and Gerry began to lead it. And then, the Beatles ended up following the steelband in another way.”

— How?

“Well the work of Liverpool bands in Hamburg is a famous part of Mersey Beat history. But the first Liverpool musicians to play in Hamburg, in 1960, were black artists: Derry Wilkie, with his group the Seniors — and the Royal Caribbean Steel Band. Gerry Gobin said to Lord Woodbine, and to Allan Williams: “This is where it’s happening, you should get the Beatles over.” So despite the apparent awkwardness in the Beatles’ early relationship with the steelpannists, Gerry, like Lord Woodbine, began to feel they deserved a chance.”6

Liverpool street view in the early 1960s

Historical negligence. You highlight the significance of Liverpool’s black community, which is nearly absent in most accounts of the Beatles’ early years...

— Are you the first person to research this topic, the Beatles’ black history?

“No. In 1998, London’s Observer newspaper ran an article by Tony Henry, emphasizing Woodbine’s role and criticizing writers on the Beatles for overlooking or downplaying this.7 Henry interviewed Woodbine and several of his contemporaries in Liverpool 8. The article goes into detail about Woodbine’s close involvement with the Beatles, but focuses more on the professional side than the music. Since Woodbine died in 2000, two of the main Liverpool writers on the Beatles — Bill Harry and Spencer Leigh — have dismissed this article.8 That is, they momentarily acknowledge its existence but imply that Woodbine was exaggerating.”

— So have most writers been dismissive of that piece as the main account of the Beatles’ links with Liverpool’s black community?

“Most books about the Beatles don’t refer to any links between the Beatles and Liverpool’s black community, and don’t mention the comments of Woodbine or his contemporaries in the article. It’s odd, really, that the article has since been overlooked elsewhere. As a prominent feature in a Sunday newspaper — that was actually syndicated around the world and reiterated elsewhere in the British press — it probably received a wider readership than most books on the Beatles. So I think it’s reasonable that readers of later biographies might expect some acknowledgement of its content.

“The most substantial response to Tony Henry’s piece on the Beatles’ links with Liverpool’s black community came from Professor Arthur Marwick, a respected British historian. He wrote to the Observer, congratulating the journalist on an excellent article.9 But Professor Marwick did point to a statement he felt was exaggeration.”

— Which was what?

“The article included a comment about Woodbine from Allan Williams — whose own role as the Beatles’ manager has been debated. Biographies refer to Williams as the Beatles’ first manager. Bill Harry acknowledges this but, closely analysing various documents, asserts that technically, Williams was the Beatles’ agent, not manager.10 Nonetheless, as Harry acknowledges, McCartney commented in 1995: “When we started off, we had a manager in Liverpool called Allan Williams [...] a great bloke, real good motivator, he was very good for us at the time.”11 In terms of history, there’s a point to be made there about the ambiguities, or interactions, between what is written down and what actually happened — and what is remembered as having happened.

“Anyway, my point is that Williams seems to have some authority on the Beatles’ early years — and he told the Observer: “Without Lord Woodbine, there’d have been no Beatles.” Professor Marwick, while praising the article, pointed out that you could say that about lots of people involved with the group.”

— And what do you think?

“Well, Stuart Sutcliffe, Bob Wooler, and Bill Harry too — all these people played important roles in the Beatles’ story in Liverpool. But their names are known; their importance is celebrated — rightly so. I think Lord Woodbine deserves some similar recognition — as a promoter of the Beatles, but more so as a musician. Some proper respect for Lord Woodbine’s role in Liverpool music is long overdue, and his importance doesn’t need exaggerating.”

— Why do you think it is that the black Liverpudlian angle on the Beatles has been neglected in books?

“I don’t know. Maybe some researchers are scared to take the risk of writing about this, fearing that if others don’t believe them, they’ll lose face. And this can spiral. Writers think: “Well if that respected book doesn’t mention it, there’s probably no substance to it.” Or, it could simply be that a lot of writers simply aren’t aware of the black perspective on the Beatles’ story that persists in Liverpool. I should add at this point that I was unfamiliar with all this until my PhD supervisor mentioned it to me.”

— Did the Beatles themselves acknowledge the influence of Liverpool’s black community though?

“Yes, but only occasionally — and no one asked them about it. Paul, as I say above, remarked that the Beatles took what they wanted from Liverpool’s diverse ethnic sounds. He also said in 1980 that in the early years they were on the look-out for a new sound, and they, like others, believed at the time that calypso was going to be the next big thing.12

— Anything else?

“Yes. According to most histories of the Beatles, it was Bob Dylan who introduced them to cannabis, in 1964. That’s widely regarded as a good thing for the Beatles’ creativity. But the Dylan story is a myth — a white myth. It was Jamaican acquaintances in Liverpool who first introduced at least two of the Beatles to marijuana, around 1960.”

— Says who?

“John Lennon said so, in 1975. Describing his early drug experience, long before meeting Dylan, he referred to his Liverpool background. It’s worth quoting what he said: “People were smoking marijuana in Liverpool when we were still kids, though I wasn’t too aware of it in that period. All these black guys were from Jamaica, or their parents were, and there was a lot of marijuana around. The beatnik thing had just happened. Some guy was showing us pot in Liverpool in 1960, with twigs on it. We smoked it and we didn’t know what it was.””13

“Now, it’s just possible that “some guy” who Lennon mentioned was not one of “these black guys” he refers to in the earlier sentence. But even so, that’s one of the most detailed comments Lennon ever made about his early acquaintance with marijuana, and he draws a direct link there to Jamaicans he knew in Liverpool. But though Lennon said this in 1975, and the quote was reproduced in the Beatles’ Anthology book (2000), this comment has not been picked up in subsequent books. It’s more of a commonplace to suggest that Lennon was introduced to marijuana not by Dylan but at the elite dinner parties of swinging London.”

— And you’re quite passionate about the importance of Liverpool black history in the Beatles’ work, aren’t you?

“Yes, very. I’m not implying that the Beatles callously took from the black community — that would be an insult to everyone. Despite the initial misgivings that Lord Woodbine and Gerry Gobin had about these Beatles, a lot of time and encouragement was generously given to the Beatles by these local black musicians. But this hasn’t been considered or even mentioned in most biographies or studies — most of which are written by white men, like me. But the thing is, most people who write books about the Beatles, again like me, were not there at the time and place.

“Now as I say, the very few writers on the Beatles who actually mention this do so extremely briefly and dismiss it. I don’t think they should be criticised for that — I’m very familiar with their work, much of which is excellent, and I’m sure that these writers genuinely believe there’s no substance to the possibility that Lord Woodbine and Gerry Gobin played significant roles in the Beatles’ early years. So these writers, I’m certain, are just doing what their consciences tell them is right, and presenting what they believe is the truth. Equally, I’m doing what my conscience tells me is right.

“Suggestions of the Beatles’ pre-1962 interest in expanding their musical sound, as made by Paul McCartney, seem entirely consistent with their with their later, 1965-8 work. So I’ve followed this up and interviewed people in Liverpool who witnessed their early years.”

— But there are other people who were actually there, and don’t believe that black musicians played any role in the Beatles’ work, or Merseybeat...

“That’s true. For example the late Bob Wooler, the Cavern’s resident DJ, influenced and witnessed the Mersey Beat scene quite closely. He said in 1998 that people were starting to go over the top in emphasizing the role of black musicians in Mersey Beat. He said this didn’t tie in with his memories.14 And he wasn’t the only person to suggest that people who emphasized the role of black Liverpudlians in the 1950s and 1960s music scene were just being ‘politically correct’.”

— And what do you think?

“Well, I respect Bob Wooler’s importance, and his opinion, but I think that he and others have been wrong here. This isn’t about political correctness — it’s about history. The importance of black music, black people, and black culture in Liverpool in the Beatles’ history isn’t a so-called ‘fashionable’ issue — it’s always been known and talked about in Liverpool. What I’m talking about is new information only because it hasn’t been acknowledged in books yet. And just to repeat, there were all sorts of influences on the Beatles’ work, from music hall to ska to Tibetan sacred music to folk to electronic music, in addition to a sound that was decidedly their own, a defining characteristic being that it changed over the years. The influence of black Liverpudlian musicians is not necessarily more or less important than these others — though it’s worth remembering that it does seem to have been the first instance of them expanding their musical style...”

— But Bob Wooler was a key figure in Mersey Beat and he wasn’t convinced by the kind of the things that you’re now saying.

“Yes, but I don’t think he was there, for example, in the Jacaranda when John and Paul gradually plucked up the courage to ask the steelpannists if they could join in — or in the New Colony Club when John would take up his guitar and start jamming with Woodbine’s steelband.15 John Lennon was a rhythm guitarist. Paul McCartney became a bass guitarist. Rhythm is vital for those instruments. And Paul is also a drummer. He often drums on his albums. He said in 1997: “I’ve been drumming for years, since the old Lord Woodbine days.”16

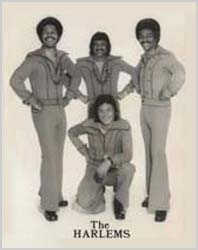

The Harlems, with Vinnie Ismail at the centre back

The chords of Vinnie Ismail. The steelpannists, you say, weren’t the only black musicians in Liverpool who John and Paul admired...

— Can you give us another example?

“Yes. I’ve also been researching the work of Vinnie Ismail, a Somali-Irish rhythm guitarist from Granby, Liverpool 8 — the area known since the 1980s as Toxteth. Vinnie was born Vincent Tow; he was born in 1942 and died in 2007. Vinnie is well-remembered in Liverpool. However, references to him online are quite disparate, because there’s some confusion about his name. He’s variously mentioned as Vince Tow, Vinnie Ishmael and Vinny Ishmael. For the record, the correct spelling is Ismail. In the period we’re talking about, though, before 1963, he would have been known to the Beatles and many other Liverpool musicians (especially guitarists) as Vince Tow or Vinnie Tow. He first performed as the leader of Vince & His Volcanoes; after this group disbanded in 1963, Vinnie went on to sing with Liverpool groups the Harlems, the Valentinos and the Handful. He also played guitar for the vocal group the Chants.”

— What did Vinnie have to do with the Beatles?

“It’s more a question of what the Beatles had to do with Vinnie. In the early 1960s, he led his group, Vince & His Volcanoes. There were various black Liverpudlian singers at the time — most famously, Derry Wilkie, and also The Chants, who the Beatles once backed at the Cavern. But Vinnie Ismail was one of very few black rhythm guitarists — he might even have been the only one then.”

— How have you learnt about Vinnie?

“Vinnie’s manager was George Roberts, who worked with Bob Wooler at the Cavern. He’s authored an article called ‘Managing the Bands’ (2001), available on Bill Harry’s Mersey Beat website. George was raised in Granby; he is Arabic-Norwegian. Of his mixed-‘race’ perspective, he writes: “... consequently and by choice, I always identified myself with the ‘contained ones’, the underdogs.” I’ve interviewed George Roberts, he’s a very interesting man. He put together and managed the Clayton Squares, and oversaw the first TV appearance by an early grouping of the Mersey Poets, comprising of Adrian Henri and Roger McGough, with musical accompaniment from John Gorman and McCartney’s brother, Mike McGear. George’s article casually describes how, one morning at the Cavern, before the doors opened, George was waiting in the Cavern for Bob, and he saw Vinnie giving Lennon and McCartney a casual guitar lesson. This was 1961.”

— What happened?

“Vinnie was showing John and Paul how to play a certain Chuck Berry chord, which they called ‘the string bar seventh’, or just the seventh. They were having trouble mastering it. The person who showed it to them was the only black guitarist on the scene.”

— Is that really a big deal?

“To George Roberts it was no big deal. Just a black musician showing two white musicians a few chords. But if you’re interested in the Beatles’ music, it’s an insightful detail. Chuck Berry was one of John’s favourite musicians. Chuck Berry’s influence on John Lennon is easily as important as that of Bob Dylan later on. And Vinnie was a link in how John learnt to play rhythm guitar in the Chuck Berry style.”

— Has anyone else written about this?

Apart from George Roberts himself, no one has yet written about Vinnie’s role in the Beatles’ development. But Mike Brocken at Liverpool Hope University, writing about the Beatles’ early years in Liverpool, makes the point that Berry songs are difficult for guitarists to master. He suggests that a mark of a good band at the time was ability to play Berry covers.17 The Beatles’ live sets contained about twelve Berry covers over the years.”

— Do you think this all stems from that one tutorial with Vinnie?

“Well that session in the Cavern wasn’t a one-off! George noticed Vinnie showing Paul and especially John guitar chords on numerous occasions. They never paid Vinnie, it wasn’t a formal arrangement. They just wanted to learn certain techniques, and he showed them. Usually, they caught up with him offstage at the Starline club on Windsor Street, which George managed. George said that his main memory of John with Vinnie is John saying: “Show me this, show me that.” And Vinnie, who seems to have been a patient and generous man, was quite happy to help out.”18

— Are you saying that without Vinnie, the Beatles wouldn’t have learnt Chuck Berry riffs?

“No, I wouldn’t say that. They’d already begun playing Berry covers. But John wanted to get the rhythm guitar part just right — so he went to Vinnie. This is important because it’s a kind of commonplace to say that the Beatles took a lot in terms of influence from American R&B, but had nothing whatsoever to do with local black musicians in Liverpool. But this isn’t just about Chuck Berry songs. John plays that seventh chord, shown to him by Vinnie, on a number of Beatles recordings. You can hear it very clearly, for instance, on their version of “Long Tall Sally”. Also, “The Ballad Of John And Yoko.” Listen to John’s rhythm guitar — that was the technique Vinnie showed him and you can hear it years later.”

Liverpool street view in the early 1960s

“Yes. Liverpool’s black culture played a role in the Beatles’ history. Lots and lots of other people influenced and helped them. But the importance of black Liverpudlian musicians has not yet been recognized in the books. I think it should be. Now I wasn’t there in Liverpool — nor were most of the people writing the books. But there’s too much oral evidence on all this for it to be ignored. And the oral evidence that we have is too consistent to be dismissed as just hearsay.”

— How is it consistent?

“Paul McCartney acknowledges in respectful terms, but not in

much detail, that Liverpool’s ethnic diversity was vital to the

Beatles’ sound. My research concentrates on what black people in

Liverpool have to say about this. George Roberts did not know

Lord Woodbine or Gerry Gobin. But they all say the same thing.

The Beatles, especially John and Paul, were always looking and

listening for new sounds to use in their music. This began in

Liverpool, and the city’s black musicians were part of it.”

read more

------------------------------------------------

Author’s note

* James McGrath would like to thank George Roberts, Mandy Smith,

Barbara Phillips, Candace Smith, Wes Paul and Peter Mills for

their assistance with and encouragement of his research.

------------------------------------------------

Notes

1. Du Noyer, 2002: vii.

^

2. For example: Norman, 1981: chapter 5);

Flippo, 1988: chapter 5.

^

3. Wes Paul, email to James McGrath, 30 July

2009. Return to text

^

4. Henry, 1998: 9.

^

5. Candace Smith, interview with James

McGrath, 7 October 2009.

^

6. Ibid.

^

7. Henry, 1998: 9.

^

8. Harry, 2000: 1164; Leigh, 2000: 6.

^

9. Mawick, 1998: 22.

^

10. Harry, 2002.

^

11. Wonfor, 1995/2003: DVD 1.

^

12. Garbarini, 1980: 156.

^

13. The Beatles, 2000: 158.

^

14. Leigh, 2002: 123.

^

15. Henry, 1998; Candace Smith, interview

October 2009. See also Roberts, 2001: 1.

^

16. Wonfor, 1997.

^

17. Brocken, 1996: 10.

^

18. George Roberts, interview with James

McGrath, 19 March 2008; email, 14 June 2008.

^

Contact Dr. James McGrath - j.mcgrath@leedsmet.ac.uk