The Saigon River glitters under moonlight, reflecting a sampan

highway for Viet Cong en route to a firefight with American

forces.

(Image courtesy Hadi Zaher)

All night long, her flaxen hair shimmying like disco lights in the full moon, the river showered its blessings on our predicament. In the pitch of the blackout, the candle on the bamboo table flickered wanly; the wick, ungraceful in the gluey wax, wasting away. I was grateful that a compassionate moon loitered on the porch while we, the matter and I, deliberated over an argument for spiritual mediation. Sleep at a chess marathon. Sleep for both of us, the matter and me, a Trini in Nam.

Now I’m seeing things that remind me of other things. This scene playing out before me – the moon river, the river moon – proves that I may have been more than a little prescient in M.P. Alladin’s art class at the British Council on upper Pembroke Street when I’d carved it in wood a mere eight years ago at the age of 12! Eventually, the flax on the downstream current glittered off and took the argument out of sight, a good ways behind the American cargo boats so big and fat down at the docks that they leave footprints in the water.

The Saigon sun was already rinsing its face in the river when we tangled out of the sofa, bedraggled like leftover trees in a storm. Like rubber trees in the Michelin Plantation following a napalm run in the Iron Triangle. I nourish no suspicion towards occult lore (though it grew up around me on Laventille hill and Behind the Bridge, a small ways from Royal Theatre), so the bellwether might well have been a nod to the order of the day, but it would take more than an omen, I swear, for me to back out of the task at hand. Any man can be saved; It would be the sermon of the day.

Fr. Brylcreem’s Cathedral, Saigon

At midday Mass in the city, something spooky turned up. I had a pull in my heart. It felt like a coachman’s twitch on the bridle, and it punched in just on time during the sacrament. Ushered along by a sip of wine, the spare little wheel from God arrived at the soul cold and damp.

All of a sudden, it seems, melancholia was sketching the mind a dull jab jab blue. Would that I could dress it in buttery pastels, like Degas’ paintings! Then I could pick up the pre-monsoon wind sweeping the aisles, then flattening out through the canted stained-glass windows to empty into the steam bath gridlock outside. Such a head trip would not be enough to lance this unholy mess or pry open the clutch on my heart. Instead, I’m left to surrender only to principles, or whatever influences the whip hand under these circumstances.

At the end of Mass, we, this grave matter and I, catch up with the Vietnamese priest in the sacristy, where truth, unhinged from conscience, summons up a surprise confession that gives the cleric enough reason to be disturbed. His olive face admitting some sag, the bantamweight priest, fortyish, at once gathers himself. Sitting at a wooden desk, small in the fullness of the twin-spired cathedral, he fidgets with thick black-rimmed glasses until the comfort zone on the bridge is secured. A small drama unfolds when he plants his elbows as a fulcrum to plop his head in stubby but delicate hands, swinging it like a pendulum on double-time.

“Americans. Americans.” he murmurs in a French-Vietnamese accent. “You Americans. So arrogant.”

Such sanctimony! In itself it carries an ironic surfeit of arrogance.

The priest affects an air of disgust, as if borrowing attitude from the pulpit. He brushes back dark, stringy, Brylcreemed hair that humidity has rearranged. Smooths limp noodles neatly into place, packs the strips of dough into his bowlish skull, the halo slipping off, tumbling down the chasm between his arched torso and the straight-backed wooden chair.

The signal is to retreat from this icky battlefield, just as a homily from the lectern at the cathedral in downtown Port of Spain begins to well up in flashback — Stephen being stoned to death in the Book of Acts. A dread story that hasn’t drifted too far from my moral consciousness. Well, ain’t that a bitch.

We are in dangerous space now, between the cape and the bull. Have we already inherited the insanity of the fight? I can’t speak for him, but this new American — they call me “Preece,” short for altar boy — is supposed to be enjoying a three-day respite from combat. Picking up new glasses, the old ones waylaid in the scramble of a rocket attack at a firebase in Phuoc Vinh.

Now, here we are, exchanging 'robber' talk— not unlike rival mafiosos — in a crevice of God's soul.

"You won't be able to get away with it."

Oh! How he merits a sniper's stare, this enemy priest. His face, all but an impotent disciple of authority is flushed. Fr. Brylcreem is now dead to my needs.

I wheel back to the sanctuary.

Darting eyes hurdle serried racks of votive candles and their wobbly lights bare-ass naked and divine amid the pious hush; beyond the early rows of pews, smart and soldierly in their close- order drill. There they are. My friends, Pinky and Maria. Their faces flash surprise at my unmistakably altered state. They worry over this ersatz assassin's blanched complexion, his peculiar grip on the dagger. They’d been keenly aware that I’d sat up all night.

Both 22, they travel as an offbeat act that crosses dogma with erotica. Maria, the coolheaded one, juggles religious and secular responsibilities. A Mexican-American nun who counsels Saigon whores.

Pinky, the passionate other, a civilian nurse, wears a prickly aura beneath gossamer charm. A wedding band, still new and shiny, wears on her right hand, though a divorce from a bomber pilot serving in the war is in the mill.

We check out of the cathedral, out of this cul-de-sac of curiosity, the swelter of Fiat cars and motocyclo traffic slapping at us like a boxer’s paw, the soot swinging back with the carriage of the priest.

His stuff.

That baggage.

The tinny voice!

Bells in the church tower strike telling blows in counterpoint.

Ha! You Americans!

In Vietnam, I am American.

In America, I’m immigrant.

In the bush, a plain ol’ grunt, door gunner and a combat controller.

The new ugly American.

Such a dichotomy! I must analyze later this strange creature, its head braided in a stars and stripes bandanna, dropped just so in the lap of my psyche. Another contretemps looms. The order of the night’s events.

Wait a minute!

Not yet.

For right now, that bright afternoon on a Christmas Day of my early teens is re-indexing itself, spitting hot shocks of neon and setting the brain on edge. A young church colleague, who, like myself, lived in a slum community, but who, unlike me, mindlessly gravitated beyond the altar, found himself in the mad embrace of a knife fight on a street Behind the Bridge.

Truth to tell, not a real bridge. More a synthetic construct without girders, a demarcation line between a city teeming with mercantile mercenaries and its victims, including teething gangs that would lop off an arm over a tart or a steelband issue.

In such an environment, yes, it was there that I lost one of my best friends.

There are no sermons for the hardships that delineate a culture at war under colonial exploitation. Not Homer’s. Not Milton’s. Not Shakespeare’s. Life in the bush shapes those born into its lore. Not that each of its denizens is prepared for death, but it continually flashes before their eyes. The brackish dry river and the polluted Gulf of Paria are one and the same tributary of horror.

So now I’m left to ponder such pop-psych trauma as a heady mix of virtue and sin. I’ve been in-country only a few months, and already a lot of us are lost in the devil’s little acre, shuttled back so soon to the States in coffins wrapped in the Stars & Stripes.

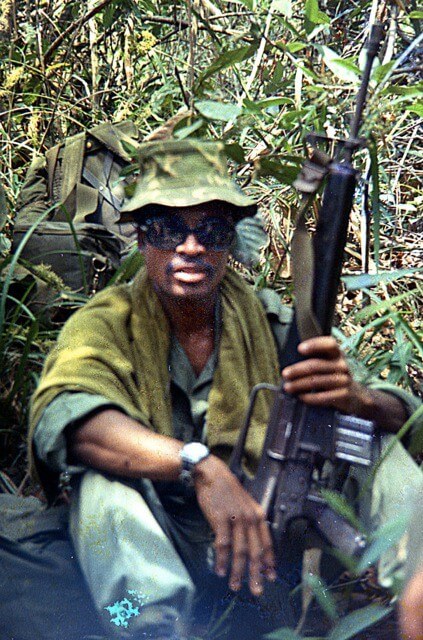

Dalton Narine on patrol in the Ho Bo Woods

Well, then, shall I kill the sonofabitch before taking Pinky to dinner? Or, for the second day, R&R at her villa, since the VC bombed the military hotel a few hours before I arrived in the city. Then what? Mindful of the 10 p.m. curfew, slingshot back to Cholon to waste him?

Him?

The enemy Vietnamese, a Viet Cong in civvies, whose sleight-of-hand rip-off at dusk during a blackmarket money transaction still addles the brain a month later?

Don’ mean Nothin, not a damn thing. Why get twisted over a few dollars more when I can shove my M60 weapon, the PIG, down your throat in a firefight?

The author gets ready to move out into the jungle from his

firebase in Phuoc Vinh.

Dalton Narine joined Trinidad All Stars as a teenage tenor panist in 1959. His father threatened to beat him up if he caught him playing the instrument, but Narine soldiered on and his dad gave in.

Dalton Narine joins Trinidad All Stars as a teenager, rehearses

the Band’s 1959 Bomb, Intermezzo, in the garret of the Maple

Leaf Club on Charlotte Street.

Dalton Narine is an award-winning writer and documentary filmmaker. He migrated to the United States and has worked as a journalist and as a writer for the New York’s Village Voice, Ebony, the Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel, and an editor for The Miami Herald. Narine, who suffers from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, is a decorated veteran of the American war in Vietnam.

Dalton Narine watched a movie among friends and was harassed for watching the credits roll. He was 12. They laughed at his quip that someday his name would be scrolling like that on a movie screen somewhere. Little did they know it was a prescient warning.

A similar scene played when Narine stopped learning the piano and walked into a panyard. Nobody believed him until they saw him playing classical music on pan on J’Ouvert. Eventually Narine co-founded the iconic PAN magazine and became senior editor.

Narine, an award-winning writer for two newspapers and a magazine, started working on a novel. But the chair of Columbia University film school steered him toward a screenplay instead. Your story is a movie, the professor said. Today Narine is working on his final draft, with two more screenplays in his head.

contact Dalton Narine at: narain67@gmail.com

Leave your comment in the WST forum